The landscape of modern manufacturing is no longer a monolith of clanking gears and rigid assembly lines. With the changing consumer needs to be more personalized, and the product life cycle becoming shorter, the manufacturing industry has changed to a paradigm that balances the sheer power of mass production of identical items and the flexibility of custom engineering. The core of this revolution is industrial automation in its programmable form, which is a key to the future of manufacturing.

In this comprehensive guide, we will peel back the layers of this sophisticated technology—exploring its definitions, its critical role in global supply chains, and how it serves as the bridge between the rigid mechanical past and the autonomous, AI-driven future of Industry 4.0.

Defining Programmable Automation: More Than Just Software Instructions

In its simplest definition, Programmable Automation is a type of automation system in which the equipment is designed with the intrinsic ability to alter its order of operations to suit various product designs change. Unlike manual labor, which relies on human dexterity, or fixed automation, which is hard-wired for a single task, programmable automation systems are “logic-led.”

But to reduce it to the simple definition of machinery that is controlled by software is to overlook the engineering complexity of it. It is a symbiotic association among three different layers of control systems that should be perfectly harmonized:

- The Brain (Control Logic): This is typically a Programmable Logic Controller (PLC). It stores the instructions that dictate the movements and logic of the system. In high-stakes production environments, the “Brain” must handle thousands of signals per second.

- The Nervous System (Communication): This includes the sensors and feedback loops that allow the machine to “know” its state. In cases where a robotic arm is required to move 45 degrees to carry out various tasks, the nervous system ensures that the movement is accurate.

- The Muscle (Actuation): These are the pneumatic cylinders and servo motors. These machine tools are programmable; they can be programmed to fit different processes depending on the program loaded.

Automation is characterized by its batch nature, which is appropriate in batch production scenarios. The system is stopped when a production run of a batch of similar items is finished. A new program is loaded, the necessary tools are altered and the system is re-booted. It is the adaptability of such systems to re-learn tasks without re-assembling the machine that makes it the foundation of mid-volume manufacturing.

Fixed, Programmable, vs. Flexible: Finding the Right Fit

The industrial strategy world does not have a “one-size-fits-all.” Making the wrong decisions regarding the types of automation may result in either wastage of capital or failure to satisfy the market demand. In order to know the position of programmable automation, we need to contrast it with its automation counterparts: Fixed (Hard) Automation and Flexible (Soft) Automation.

The Three Pillars of Automation Comparison

| Feature | Fixed Automation (Hard) | Programmable Automation | Flexible Automation (Soft) |

| Production Volume | Very High (Millions of units) | Medium (Batches of 100s–1000s) | Low to Medium |

| Product Variety | Extremely Low (One design) | Medium (Multiple variations) | High (Mixed production) |

| Investment Cost | Highest initial hardware cost | Medium to High | Very High (Due to sensors/AI) |

| Changeover Time | Impossible or very long | Significant (Minutes to Hours) | Virtually Zero (Instant) |

| Flexibility | None (Single purpose) | High (via Reprogramming) | Maximum (Real-time adaptation) |

| Typical Equipment | Transfer lines, Dial indexers | CNC Machines, Industrial Robots | FMS, AGVs, Smart Conveyors |

| Lifecycle Value | Low (obsolete after product) | High (multigenerational) | Highest (totally adaptable) |

Pros and Cons of Each Approach

- Fixed Automation

- Advantages: It is the cheapest per unit since it is very fast and efficient. Various operational workflows do not experience a processing lag since the mechanical order is predetermined.

- Disadvantages: It is “brittle.” Even a minor modification in the design of the product can make the entire line useless. A lack of flexibility inhibits this manufacturing operation.

- Best For: The everyday assembly line producing commodities where the design is frozen for years.

- Programmable Automation

- Advantages: It provides greater flexibility and the “freedom to pivot.” It enables firms to cater to various niche markets with the same floor space.

- Disadvantages: It involves a high initial investment. The machines are not utilized when there is a frequent product changes and this should be well managed in order to make a profit.

- Best For: Industrial components and medical devices.

- Flexible Automation

- Advantages: The “Holy Grail” of the production process. Product A can be produced, followed immediately by Product B.

- Disadvantages: The high costs and complexity make the ROI far more difficult to justify for many mid-sized companies.

- Best For: High-end custom manufacturing and aerospace.

Real-World Examples: CNC Machines, Robotics, and PLCs

To see the capabilities of programmable automation in action is to see the physical manifestation of digital logic.

- CNC (Computer Numerical Control) Machines: A CNC mill is a classic example of a programmable tool. By changing the G-code (the program) and the cutting tool, the same machine can execute precise machining tasks, carving an aluminum engine block in the morning and a delicate brass instrument component in the afternoon.

- Industrial Robotics: A 6-axis robotic arm is physically identical whether it is welding a car frame or palletizing boxes of cereal. The distinction lies in the fact that the “End Effector” (the hand) and the software that is programmed into its controller. The traditional pick and place fixed machines do not have the 3D spatial flexibility that robots offer.

- PLCs (Programmable Logic Controllers): These are the ruggedized computers that act as the conductors of the industrial orchestra. Unlike a home PC, a PLC is designed for extreme heat, electrical noise, and vibration. They take inputs from sensors and execute logic to control motors and valves. Because they are modular, a factory can reconfigure its entire logic flow just by updating the PLC code.

Why Batch Production Thrives with Programmable Systems

The benefits of programmable automation are evident in a world where “Mass Customization” is the new reality. Companies rarely manufacture the same product ten years in a row, but they could make a batch of electronic sensors or even a batch of baguettes in the contemporary food processing.

Direct Scenario: The Power of Reprogramming vs. Rebuilding

Take an example of an industrial pump manufacturer. They manufacture pump housings of five sizes.

- In a manual scenario, the labor cost per pump is too high to be competitive in a global market.

- In a fixed scenario, they would need five separate assembly lines—a massive waste of space and capital, especially if the “Size Large” pump only sells 200 units a year.

- In a programmable scenario, they use a single robotic cell to launch new products rapidly.. When the order for 500 “Size Small” housings is done, the technician spends 30 minutes loading the “Size Medium” program and adjusting the grippers.

Cost-Saving Strategy: The amortization of hardware is the main value proposition. The cost savings are enormous with the same $200,000 robot producing 10 products in its lifetime. This “Software-Defined Manufacturing” allows even medium-sized businesses to compete on the international level. In addition, the hardware is reusable in the next generation, which demonstrates that such systems yield significant cost savings in the long run.

Integrating AI and IoT into Modern Programmable Systems

The potential scope of programmable automation is expanding through Artificial Intelligence and the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT). This enables systems to handle “semi-structured” environments. With AI, the system “sees” deviations, maintaining high production rates and product quality without human intervention.

Traditionally, a programmable machine followed a strict, linear path: If Sensor A is triggered, move Arm B to Position C. The machine would crash or enter an “emergency stop” state in case of an unexpected occurrence like a component being slightly misplaced or a foreign object entering the working zone.

The AI Revolution: Cognitive Automation

Computer Vision and Machine Learning have become part of modern systems. A robot does not need to be programmed to know a specific coordinate (e.g. X = 10.5, Y = 20.2), but rather it can be trained to identify the shape of an object using thousands of training images. If the object arrives on a conveyor belt tilted at an odd angle, the AI calculates the necessary trajectory adjustment in real-time. This reduces the time spent on “fussy” programming and makes the system resilient to the messy reality of a factory floor.

This transformation of the inflexible coordinate-based logic to the perception-based logic allows programmable systems to handle the so-called “semi-structured” environments. To give an example, in a traditional system, a movement of a component by as little as 5 millimeters would lead to a crash or loss of grip of the component by the machine. With AI-enhanced programmable automation, the system “sees” the deviation and adapts its pathing instantly, maintaining high throughput without human intervention.

The IoT Connection: The Connected Factory

Manufacturers can access Predictive Maintenance by linking programmable machines to the cloud for continuous data collection.

- Sensor Fusion: Vibration sensors on a motor send data to an IoT gateway.

- Anomaly Detection: The algorithms detect that the frequency of vibration of the motor has changed by 0.5Hz, which is an indicator of bearing wear.

- Actionable Intelligence: The system alerts the operator to schedule maintenance. This synergy turns “dumb” automation into a “smart” ecosystem that optimizes operational efficiency.

Evaluating the ROI: Balancing High Investment and Flexibility

The decision to implement programmable automation is rarely purely technical; it is a financial calculation of Risk vs. Agility. The Return on Investment (ROI) for these systems isn’t just about “replacing workers”; it’s about “expanding the factory’s potential.”

The Investment Components

- Capital Expenditure (CAPEX): The upfront cost of the robots, CNC units, PLCs, and high-precision actuators.

- Software & Integration: This is the cost that is typically the hidden one. Even the code, the HMI (Human-Machine Interface) and the connection of the machine to the existing ERP (Enterprise Resource Planning) systems may be as expensive or even more expensive than the hardware.

- Training & Culture Shift: The employees must alter their mentality of being operators (button pushing) to technicians (logic management). This requires heavy investment in human capital.

The Flexibility Dividend

The real ROI is observed when you take into consideration the Product Lifecycle. A 10-year programmable system can be reconfigured 6 or 7 times to entirely different products in a market where consumer preferences are changing every 18 months. A fixed system would have been scrapped or sold at pennies on the dollar 5 times over. Therefore, the Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) of programmable automation may be considerably lower than any other manufacturing process in the long-term (10 years). It allows a company to say “Yes” to new low-volume contracts that would not have been feasible with rigid machinery.

Avoiding Pitfalls: Why Programmable Automation Projects Fail

Although it has its advantages, the road to a fully automated facility is full of costly failures. Studies indicate that almost 30% of automation projects do not achieve their initial objectives. Every strategic leader must be aware of these traps. Most of the failures can be attributed to the lack of “systemic thinking”-focusing on the glamorous aspect of the robot arm, the arm, and ignoring the boring aspects that make the system reliable.

- The Complexity Trap

The majority of companies design their programs to the extent that it requires the original system integrator to debug them. When such an integrator is no longer available, the system becomes a “black box” that no one is willing to touch, and the system begins to rot as features are disabled because no one knows how to fix them.

- Poor Component Reliability

A programmable system is a chain, and it is only as strong as its weakest sensor. A single, low-quality, uncertified proximity switch, unable to sustain the heat of a 24/7 production cycle, supplying a $50,000 robotic arm, causes the entire million-dollar production line to come to a stop. Electrical noise and sensor fatigue are the most common causes of a programmable environment where sequences change often, leading to the occurrence of phantom errors.

- Ignoring the Power of a “One-Stop” Supply Chain

This is where strategic sourcing comes in as a competitive advantage. Intelligent engineers would enlist the assistance of partners like OMCH to minimize project failure. Since its establishment in 1986, OMCH has expanded to become an international automation and low-voltage electrical products powerhouse.

The OMCH Advantage in Programmable Systems:

When creating a programmable architecture, the majority of the “bugs” are located in the power, sensing and control integration. OMCH deals with this through their philosophy of “One-Stop” which offers a massive portfolio of over 3,000 SKUs that are designed to be compatible with one another.

For a project manager or lead engineer, the value is clear:

- Global Trust & Presence: Serving over 72,000 customers across 100+ countries, OMCH products are battle-tested in every climate and industrial sector imaginable.

- Certified Reliability: Their products are of high international standard such as IEC, GB/T, CCC, CE, RoHS and ISO9001. This will make sure that your programmable system will not fail because of poor electrical parts that cannot withstand the “noise” of a modern factory.

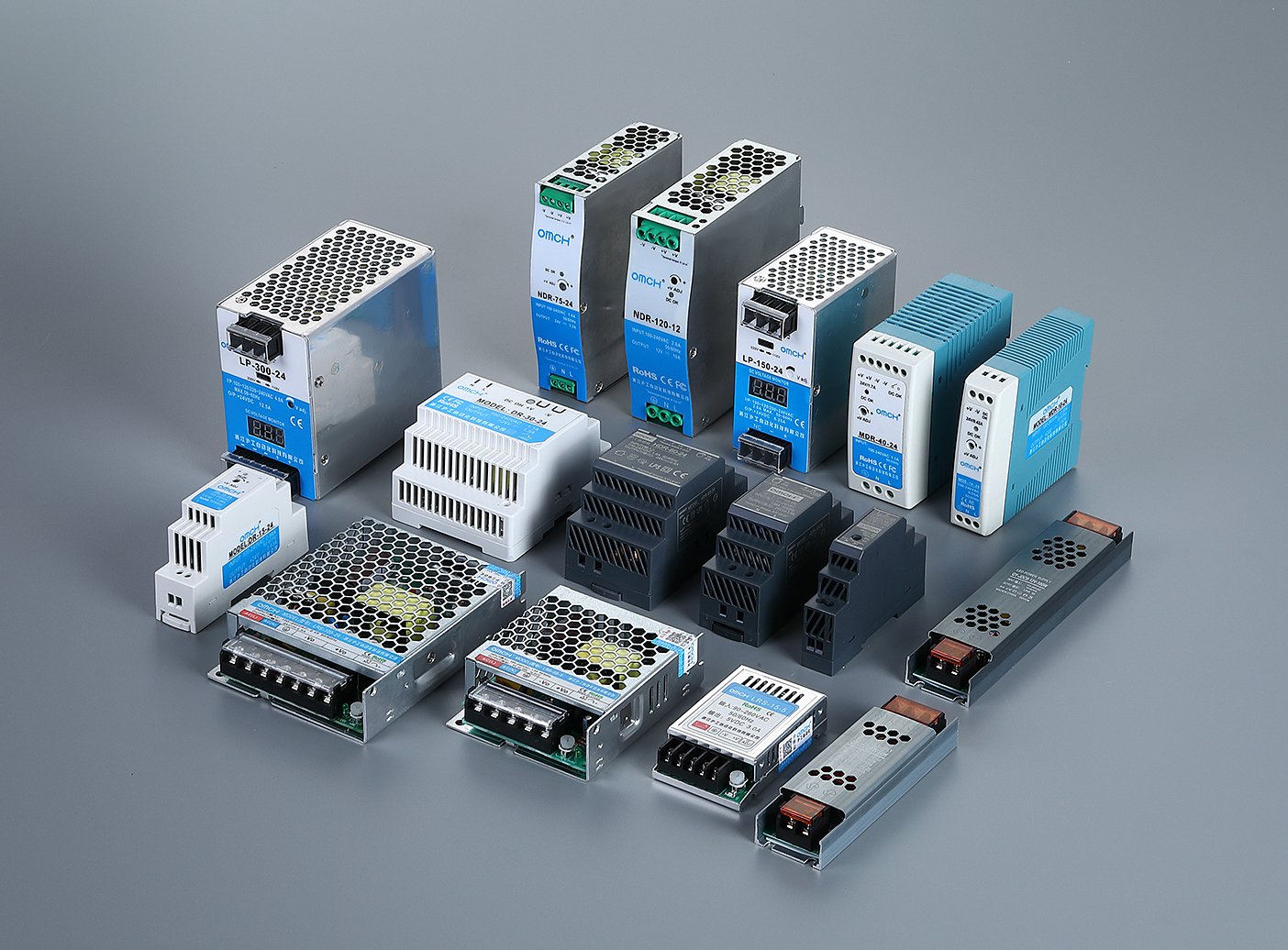

- Unrivaled Product Breadth: OMCH covers the entire “Nervous System” and “Muscle” of your machine—from Switching Power Supplies (AC-DC, DIN Rail, Waterproof) and Sensors (Inductive, Capacitive, Photoelectric) to Pneumatic Cylinders, Solenoid Valves, and Rotary Encoders.

- Service & Support: They have 86 branches in China and a distribution network in 70+ countries, which means that they can offer the local support and 24/7 fast response needed to keep a programmable line running. Their quality compensation measures and “One-Year Warranty” provide the confidence that a project requires in the high-stress period of “commissioning.”

The manufacturers can minimize the “integration friction” and supply chain delays that have led to the failure of so many automation projects to meet their budgets and deadlines by selecting a partner with 7 dedicated production lines and an 8,000 sqm modernized facility.

The Technical Challenges: Programming Complexity and Downtime Costs

Had programmable automation been simple, all garage workshops would be black factories. The technical challenges are also still high especially on the Human-Machine Interface (HMI) and the physical physics of changeover.

The Programming Burden

The code that is written in an industrial setting is completely different to the code that is written in a mobile application. It should be “deterministic,” that is, it should do precisely the same thing, each time, millions of times without a “memory leak” or a crash.

- Safety Logic: A large portion of the code in a programmable system isn’t for moving the machine, but for stopping it. Calculating safety distances and light curtain responses requires specialized “Safety PLCs” and rigorous logic.

- The Cost of a Bug: In a CNC program, a decimal point in the wrong place isn’t a crashed browser; it’s a shattered spindle, a ruined $10,000 workpiece, or a workplace injury.

The Downtime Dilemma

As stated above, the “Batch Changeover” is a non-productive time. When a machine requires 4 hours to change over and only operates 8 hours, the efficiency is pathetic. World-class manufacturers aim at SMED (Single-Minute Exchange of Die). This involves:

- Standardization: Using the same mounting plates and electrical connectors so that sensors and grippers can be “hot-swapped” without re-wiring.

- Virtual Commissioning: Using Digital Twins to test the new program in a virtual environment before it ever touches the physical machine. This ensures the first “real” part is perfect.

- Modular Tooling: Using “Quick-Change” pneumatic systems where a robot can drop its welding torch and pick up a vacuum gripper in seconds.

The winning companies in this space are the ones that consider the “Changeover Time” as a fundamental KPI (Key Performance Indicator) that must be brutally optimized by technical accuracy.

Strategic Implementation: Moving from Manual to Programmable Success

Transitioning a facility to programmable automation is a marathon, not a sprint. A successful implementation follows a strategic roadmap designed to minimize risk:

Step 1: Identify the “Batch” Pain Point

Don’t automate everything at once. Start with the process where you have the most product variation but enough cumulative volume to justify the CAPEX. Look for “high-mix, medium-volume” tasks that are currently bottlenecking your output.

Step 2: Modularize Your Hardware

Avoid “Custom-Built” machines that are too specialized. Instead, buy a general-purpose robotic arm or a standard CNC base. Spend your customization budget on the “End of Arm Tooling” (EOAT) and the sensors. This ensures that if the product fails in the market, your $200,000 investment isn’t a paperweight—it just needs a new gripper and a new program.

Step 3: Invest in the “Support Ecosystem“

A machine is only as “smart” as the data it receives. Ensure your power grid is stable using high-quality DIN rail power supplies and your sensors are robust enough for the environment. Use OMCH’s 3,000+ SKUs to ensure that every minor component—from the limit switch to the counter—is of industrial grade.

Step 4: Upskill Your Workforce

Shift your staff from “doing the work” to “managing the process.” A worker who used to manually weld can be trained to be a “Robot Supervisor.” This transition increases employee retention by providing a higher-value career path and builds a high-tech culture that attracts top talent.

Step 5: Iterative Scaling (The “Pilot” Method)

Start with one programmable cell. Perfect the changeover process. Measure the ROI and the “Actual vs. Predicted” downtime. Then, use those learnings as a template to scale across the entire factory floor.

Conclusion

The concept of programmable automation is a radical change in the philosophy of industry, replacing the inflexible machinery with a flexible, software-defined future. This is an effective solution that enables factories to handle diverse products by enabling them to be reconfigured. The competitiveness in the digital age is a minimum requirement of the effectiveness of programmable automation systems. With the digital control and the high-quality elements, the businesses will be able to strike a balance between the mass production and craftsmanship, which will guarantee the quality of the products in the years to come.