The electromechanical relay (EMR) is one of the most basic components of the large ecosystem of industrial applications and circuit design, and it is also one of the most misconceived. Although solid-state alternatives have appeared, the EMR remains the basis of the modern control circuit (be it heavy industrial machinery or precision automotive electronics). It is necessary due to its ability to provide complete galvanic isolation and switch high-power loads via a low-power electrical signal.

Nevertheless, the improper choice of the relay may cause disastrous failures of the system, such as contact welding, coil burnout, and signal interference. This manual is an ultimate guide for engineers, procurement officers, and technicians. We will dismantle the mechanics of the electrical relays, analyze the critical differences between mechanical and solid-state options, and provide a step-by-step framework for selection. By the end, you will have a complete understanding of the electromechanical relay working principle and how to troubleshoot common issues.The Anatomy and Working Principle of Electromechanical Relays

The Anatomy and Working Principle of Electromechanical Relays

At its core, an electromechanical relay is a magnetically operated switch. The fundamental design relies on electromagnetic principles established in 1835 by Joseph Henry, the American scientist historically recognized as the figure who invented the electromechanical relay. Even today, this component bridges the gap between the digital world of logic (microcontrollers, PLCs) and the physical world of power (control panels, motors, heaters, lights).

Understanding the internal anatomy is the first step to mastering reliable operation:

- The Coil (The Actuator): This is a wire, which is wound around a soft iron core. Ampere Law When current is passed through this coil, it produces a magnetic field.

- The Armature (The Moving Part): A movable iron plate positioned near the coil. When the coil is energized, the magnetic field attracts the armature, overcoming the tension of a return spring.

- The Contacts (The Switch): These are conducting points that are connected to the armature and they close or open the high-power circuit.

- The Spring (The Reset Mechanism): When power to the coil is cut, the magnetic field collapses, and the spring forces the armature back to its resting position.

The Physical Hysteresis:

An often-overlooked aspect of relay operation is hysteresis. The voltage required to pull the armature in (Pickup Voltage) is always higher than the voltage at which it releases (Dropout Voltage). As an example, a 12V relay may switch at 9V and not switch until the voltage falls below 3V. This mechanical latching effect prevents the relay from “chattering” (rapidly switching on and off) if the control voltage fluctuates slightly.

Relay Classifications: 6 Core Dimensions Explained

A “relay” is a term that encompasses a colossal range of elements used in various applications. To select the right unit, we must place them into six dimensions.

By Working Principle (With Pros & Cons)

Despite the fact that this guide is dedicated to EMRs, one should learn about the landscape of various types.

- Electromechanical Relays (EMR): The standard type of relay described above.

- Pros: Low cost, totally electrically isolated, can survive voltage transients/surges, no heat sink needed. One of the main advantages of electromechanical relay technology is its robust nature.

- Cons: Mechanical wear leads to a finite life cycle; switching speed is slower (ms range); audible noise.

- Solid State Relays (SSR): Uses semiconductors (thyristors/MOSFETs) to switch loads with no moving parts.

- Pros: Infinite mechanical life, silent operation, ultra-fast switching.

- Cons: Higher cost, generates significant heat (requires heat sinks), susceptible to voltage spikes, leakage current exists even when “off.”

- Reed Relays: These are two reeds, which are of a magnetic nature, and are placed in a glass tube.

- Pros: Hermetically sealed (suited to hazardous conditions), quick.

- Cons: Only capable of dealing with very low currents (signal level) often seen in telecommunications equipment.

By Application Scenario (Automotive & Safety)

- General Purpose: Standard relays used in HVAC, appliances, and basic automation systems.

- Automotive Relays: Specifically engineered to withstand the harsh vibration, temperature fluctuations (-40°C to +125°C ambient temperature), and 12V/24V direct current systems of vehicles.

- Safety Relays: Critical in industrial environments (e.g., E-Stops, light curtains). They are force-guidedcontacts and therefore, when a normally open (NO) contact fuses, a normally closed (NC) contact cannot fuse mechanically. This allows the monitoring system to detect a fault and prevent the re-start of a machine.

By Actuation: Monostable vs. Latching

- Monostable (Non-Latching): The relay stays in its active state only while current flows through the coil. It returns to default in case of power loss. This is the safety standard of most machinery.

- Latching (Bistable): The relay uses a pulse to switch states and mechanically or magnetically “locks” into that position. It requires a second pulse (or reverse polarity) to reset. They save power in battery-operated low power devices but are dangerous in the case of equipment that must be shut down when the power is cut off.

By Contact Configuration (NO, NC, CO)

- NO (Normally Open / Form A): The circuit is disconnected when the relay is off.

- NC (Normally Closed / Form B): The circuit is connected when the relay is off.

- CO (Changeover / SPDT / Form C): Features a common terminal that switches between a NO and NC contact. These changeover contacts provide the most flexible arrangement.

By Package and Mounting Style

- PCB Mount: Pins are soldered directly onto a circuit board, common in consumer electronics.

- Plug-in / Socket Mount: The relay plugs into a base (DIN rail mounted). This is the industrial standard as it allows the maintenance teams to replace a worn out relay in several seconds without soldering.

- Panel/Flange Mount: Bolted directly to a chassis, usually for high-vibration environments.

By Load Capacity (Signal to Power)

- Signal Relays: < 2A rating. Contacts are often gold-plated to prevent oxidation from blocking low-voltage signals.

- Power Relays: 10A–30A rating. Designed for switching motors and heaters in power systems.

- Contactors: > 30A. Technically, contactors are a different category, but in practice are giant relays which are used to switch high voltage or high power.

Electromechanical Relay vs. SSR: A Deep Dive Comparison

The dilemma that engineers are presented with is usually: Do I stick with a conventional EMR or upgrade to an SSR? Even though SSRs are modern, EMRs remain the most preferable in terms of specific applications in general industrial automation due to thermal and cost efficiency.

The critical comparison presented in the table below will help you make your decision:

| Feature | Electromechanical Relay (EMR) | Solid State Relay (SSR) | Winner |

| Initial Cost | Low | High (2x to 10x cost of EMR) | EMR |

| Heat Dissipation | Negligible (Runs cool) | High (Requires bulky heatsinks) | EMR |

| Electrical Isolation | Excellent (Air gap) | Good (Optical/Galvanic) | EMR |

| Overload Tolerance | High (Can survive brief surges) | Low (Semiconductors fail instantly) | EMR |

| Switching Life | Limited ($10^5$ to $10^7$ cycles) | Infinite (if operated within spec) | SSR |

| Contact Resistance | Very Low (mΩ range) | Higher (Voltage drop occurs) | EMR |

| Switching Speed | Slow (5ms – 25ms) | Fast (<1ms or Zero-crossing) | SSR |

| Failure Mode | Usually Open (Safe) | Usually Shorted (Dangerous) | EMR |

The Verdict: For high-frequency switching (e.g., PID heater control pulsing every second), use an SSR. For general on/off control, safety circuits, and motors starting where heat space is limited, the Electromechanical Relay is still king.

Understanding Inductive Loads and Contact Protection Circuits

A 10 “Amps” rated relay does not necessarily have the ability to run a 10 Amp motor. This is the most common cause of relay failure across diverse industrial scenarios.

The Physics of Inductive Kickback: When a relay disconnects a resistive load (like a heater), the current stops instantly. However, when it opens a load inductive (e.g. a motor, solenoid or other relay coil) the magnetic field stored in the load collapses. This generates a very large reverse voltage spike (Back EMF) of thousands of volts.

V = L (di/dt)

This voltage spike leaps over the relay contacts of the opening contacts forming an electric arc. This arc acts like a miniature plasma cutter, pitting the contact surface, causing carbon buildup, or welding the contacts together.

Derating and Protection:

- Derating: A relay rated for 10A Resistive Load (AC1) might only be rated for 2A Inductive Load (AC15). Always remember to check the datasheets of motor ratings (HP ratings).

- Protection:

- Flyback Diode: Placed across DC loads (reverse biased) to recirculate the energy.

- RC Snubber: This is put across AC loads to absorb the energy.

- Varistor (MOV): Clamps voltage spikes for high-power AC loads, functioning similarly to overload protection devices.

Driving Relays with Microcontrollers (Arduino/ESP32) and PLCs

Modern control systems rarely drive relays directly.

- The Problem: An Arduino GPIO pin outputs 5V at ~20mA. A typical 12V industrial relay coil requires ~40-100mA. Direct connection will ruin the microcontroller (or other electronic devices).

- The Solution: Use a driver’s circuit. A transistor (BJT or MOSFET) acts as a switching element. The microcontroller activates a signal to the transistor base/gate and the transistor activates the greater current/voltage to the relay coil.

- Isolation: To ensure reliability in industry, an Optocoupler should be used between the microcontroller and the transistor to ensure that noise on the relay coils does not reset the processor.

Step-by-Step Guide to Selecting the Right Electromechanical Relay

Selection is not just about matching voltage; it is about matching the component to the environment and the lifecycle requirements of your specific deployment environment.

Matching Voltage and Current Ratings

- Coil Voltage: Must match your control system (e.g., 24VDC for standard industrial cabinets, 12VDC for automotive, 110/220VAC for building mains).

- Contact Rating: This must exceed your load current. Rule of thumb: Select a relay with a rating 30% higher than your steady-state load to handle inrush currents.

Choosing the Correct Contact Material

Not all “silver” contacts are created equal. The alloy used is of much importance in the welding and arcing resistance of the relay.

| Contact Material | Characteristics | Best Application |

| AgNi (Silver Nickel) | Good electrical conductivity, low contact resistance. | Resistive loads, general signal switching. |

| AgCdO (Silver Cadmium Oxide) | Excellent arc resistance. Note: Non-compliant with RoHS in many regions. Non-compliant for many typical applications. | Older heavy inductive loads. |

| AgSnO2 (Silver Tin Oxide) | Superior anti-welding properties, high heat stability, RoHS compliant. | High inrush currents (Motors, LEDs), Industrial automation. |

| Ag + Au (Gold Plated) | Prevents oxidation layer formation. | Low-level logic signals, infrequent switching. |

Recommendation: For industrial machinery involving motors or capacitive loads (LED drivers), prioritize AgSnO2 contacts to prevent early failure.

The Importance of Manufacturer Quality Control

The industrial sector is directly proportional to the lineage of the manufacturer in terms of the quality of the parts. A relay can look the same on the outside. However, internally there can be differences in the tension of the springs or the location of the moving contacts, which lead to premature failure.

Do not just look at the datasheet when choosing a supplier. You must have a partner who has a good manufacturing ecosystem. In order to exemplify this, OMCH, which was founded in 1986, has taken decades to perfect the art of production of automated parts.

- Consistency: OMCH has more than 72,000 customers around the globe and to make sure that the 10 000 th relay manufactured is the same as the first one, the company has 7 special production lines.

- Certified Reliability: Look for manufacturers that hold IEC, CE, CCC, and ISO9001 certifications. These are not just logos; they guarantee that the relays have undergone rigorous lifecycle testing (electrical and mechanical).

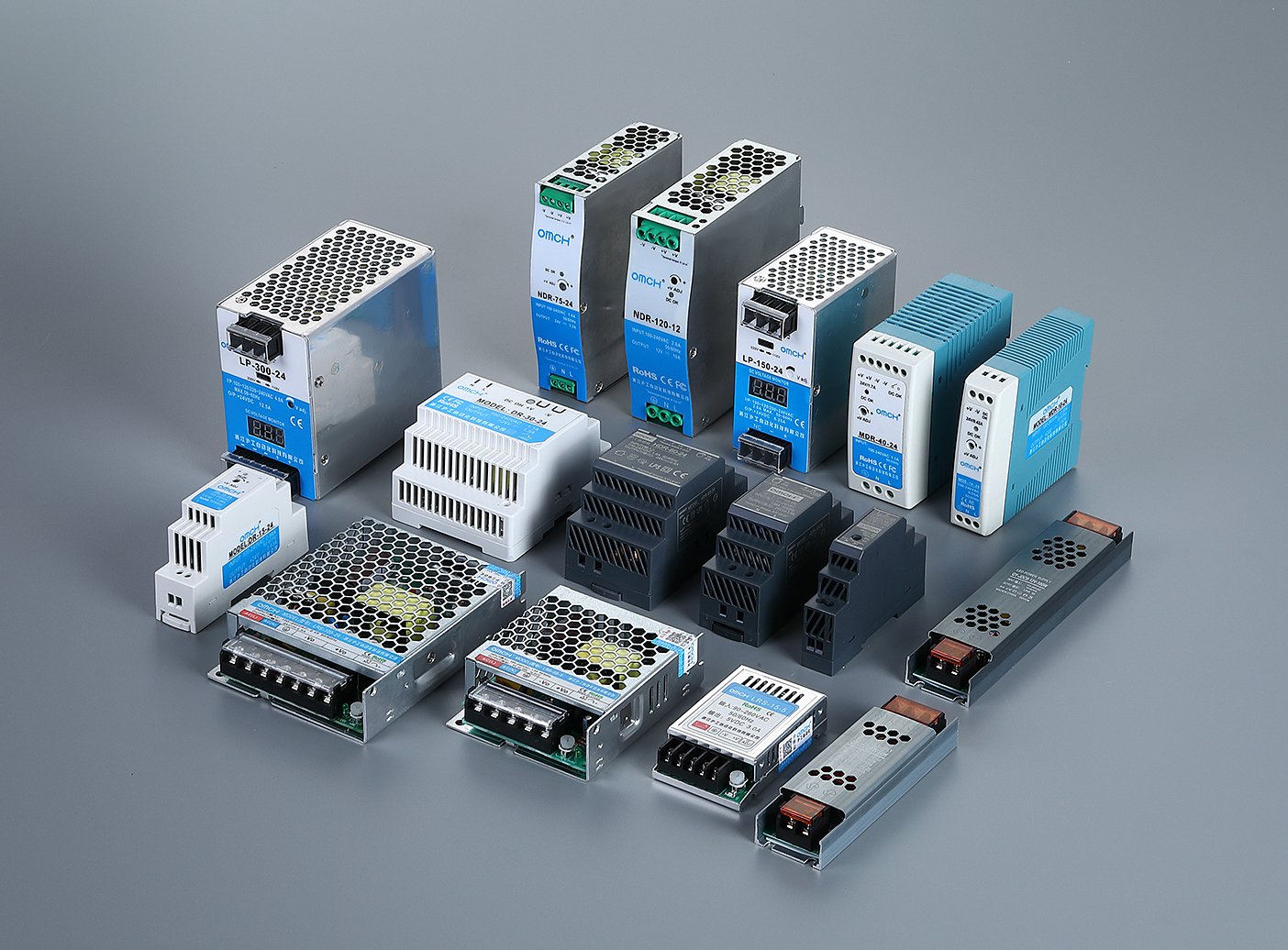

- One-Stop Procurement: Procurement managers will greatly benefit from the simplification of the supply chain. Not only does OMCH have a “One-Stop” advantage in the supply of relays (over 3000 specifications), but also the sensors, power supplies and distribution components, which interface with them. This makes it compatible and easier to provide after sales services.

Environmental Considerations (Sealed vs. Vented)

- Flux Tight: Protects against soldering flux but not washing.

- Wash Tight (Sealed): Epoxy sealed. Necessary if the PCB undergo immersion cleaning.

- Vented: Standard for plug-in relays. Enables the escape of the ozone produced by arcing, and increases the contact life in high-power switching.

Troubleshooting, Maintenance, and Common Failure Modes

Even the finest relays will not do. Early detection of the symptoms will be done avoiding downtime.

Maintenance Tip: Relays are consumables. They must be changed proactively not only when they fail, in critical applications, depending on the number of cycles or contact position wear.

Diagnostic Matrix:

| Symptom | Probable Cause | Recommended Solution |

| Relay “Clicks” but Load is OFF | Carbon buildup on sets of contacts (High Resistance). | Check voltage drop across contacts. If >0.5V, replace relay. Check if load is too low for contact material (wetting current). |

| Load Stays ON after Power Cut | Micro-welding of contacts due to inrush current. | Immediate Safety Hazard. Replace relay. Upgrade to AgSnO2 contacts or add inrush current limiters. |

| Coil gets extremely hot / Burnt smell | Over-voltage on coil or environmental heat. | Check control voltage. Ensure relay coil rating matches supply (e.g., don’t put 24V on a 12V relay). |

| Buzzing / Chattering Noise | Insufficient coil voltage or AC coil shading ring broken causing erratic armature movement or weak magnetic force. | Check for voltage dip on the control line. If driving an AC coil with DC (or vice versa), correct immediately. |

Conclusion

The electromagnetic relay is still a staple of industrial control, with a special combination of electrical isolation, high-power switching, and affordability that cannot always be matched by solid-state alternatives. But the component alone does not ensure system reliability; it depends on a very accurate knowledge of the load characteristics, contact materials, and protection circuits. The most frequent failure modes such as welding and arcing can be reduced by engineers who learn to choose contact alloys, i.e., to match them to certain inrush currents, and by proactive maintenance measures. Finally, the effective implementation of this critical element is anchored on the transition from the higher level of basic voltage ratings to the comprehensive requirements of different applications and output circuit design.