With the fast changing environment of Industry 4.0, advancement of science and the advent of computers have essentially transformed the manufacturing floor. Sensors are the eyes of the modern factory today and one of the most versatile sensors is the type of sensor referred to as the photoelectric sensor. These optical sensors are a necessity in industrial automation and they offer the ease of control and accuracy needed to do complex tasks. To select the most suitable photoelectric sensor to use in a particular application, it is important to know the various types of photoelectric sensors in the market and how these devices operate.

The presence of target objects at high speeds, e.g. beverage bottles on a conveyor belt, the safety of an automated elevator door, or the verification of the proper position of a microchip, can be detected with a photoelectric sensor. These machines present the vital information necessary to make automated decisions in different production lines.

But what do these devices perceive their surroundings? The basis of the work of these devices is based on a full description of the interaction of quantum physics, optical engineering, and high-speed electronics. Photoelectric sensing is non-contact (unlike common contact temperature sensors or mechanical switches) and can be used to detect an external object without physical wear. This tutorial is a complete explanation in how a photoelectric sensor works, the various types, and the applications of the new sensors that define the current technology.

How Photoelectric Sensors Convert Light into Electrical Signals

A photoelectric sensor is a transducer at its most basic level. It transforms electromagnetic energy, in the form of light in the visible light or infrared spectrum, into an electrical signal which a PLC (Programmable Logic Controller) can understand to complete the detection of the presence of target objects.

This process is based on the Photoelectric Effect as the basic physical process. When the receiving element of the sensor receives beams of light (photons), they give the electrons energy. When the energy is adequate, it pushes these electrons aside and a stream of electric current is produced.

In a modern industrial sensor, this conversion happens within a photodiode or a phototransistor.

- Photon Absorption: The emitted light by the emitter light source hits the P-N junction of the receiver.

- Carrier Generation: The absorbed energy creates electron-hole pairs, which can influence the base current in an internal transistor circuit.

- Signal Conversion: This change in electrical state is processed by an internal amplifier. The sensor compares the optical signals against a predefined threshold. If the brightness of the LED reflected back exceeds this threshold, the sensor “triggers,” changing its output state. This process occurs in a minimal amount of time, resulting in a rapid response time.

Anatomy of a Sensor: Emitters, Receivers, and Internal Circuitry

A photoelectric sensor is a complex combination of three main functional blocks that define the basic performance of a photoelectric sensor:

- The Emitter (The Light Source)

In the majority of modern sensors, different types of LED (Light Emitting Diodes) or laser sensors are used. Although an infrared LED is commonly employed due to its ability to resist ambient light, laser light is preferred due to its long-range capability due to a highly collimated beam. The concept of laser sensors permits a very small beam angle, which is essential in detecting small parts.

- The Receiver (The Detector)

The optical lens and photodetector make up the receiving element. The lens is necessary because it focuses the rays of light that come in on a small sensing surface. The receiver can also focus reflected light on the target with great accuracy by adjusting the angle range of the internal optics, and be insensitive to the ambient interference, including the flash of cell phones or high-frequency overhead lighting.

- Internal Circuitry and ASIC

After the detector receives the emitting light, the internal ASIC involves:

- Modulation/Demodulation: The emitter pulses its light at a specific frequency to prevent interference.

- Amplification: Increasing the micro-signals into a usable electric current.

- Sensitivity Adjustment: Allowing users to exclude minor particles like dust while still capturing the external object.

Mastering the Three Standard Sensing Modes and Their Trade-offs

The operation mode of a sensor is determined by the position of the emitter and receiver. There are three main types of photoelectric sensors applied in industry:

Through-Beam (Opposed)

The emitter and the receiver are separate units. The sensor is activated by the absence of an object between them; when an object passes through, the beam is broken. Specialized versions of this include the light curtain; the applications of safety light curtains are widespread in protecting workers from robotic arms.

- Pros: Works over long distances (up to 100m+); highest reliability in difficult operating environments.

- Cons: Requires wiring to two different places.

Reflective Type (Retro-reflective)

The receiver and emitter are housed together. The emitted light is directed to a special “reflector” and reflected back. A high-precision version is the fork sensor, where the emitter and receiver are pre-aligned in a U-shaped housing.

- Pros: Requires wiring to only one side; covers a wide range.

- Cons: Can be tricked by shiny objects unless polarized.

Diffuse-reflective Type

Similar to the reflective type, but with no reflector. The sensor waits until light bounces back from the target itself. In tight spaces, the application of fiber optic cables allows the light to reach the target through a thin, flexible conduit.

- Pros: Easiest installation; no secondary parts.

- Cons: Very dependent on the different physical properties of the object, such as color and texture.

Comparison Table: Standard Sensing Modes & Industrial Applications

| Feature | Through-Beam (Opposed) | Retro-reflective Type | Diffuse-reflective Type |

| Max Range | Very High (up to 100m+) | Medium (up to 15m) | Short (up to 2m) |

| Target Type | Any opaque object | Non-shiny (standard targets) | High-reflectivity surfaces |

| Installation | Complex (Requires 2 units) | Moderate (1 unit + Reflector) | Simple (Single unit only) |

| Reliability | Excellent (Best for harsh env.) | Good (Standard industrial) | Moderate (Color sensitive) |

| Common Applications | Long distances logistics, security gates, and difficult operating environments (e.g., car washes). | High-speed production lines, conveyor belt sorting, and detection of target objects like pallets. | Small part counting, robotic arm positioning, and color recognition devices for packaging. |

Advanced Technology: Background Suppression and Specialized Detection Modes

As automation challenges grow, the different types of sensors have become more specialized.

Background Suppression (BGS)

BGS sensors solve the biggest weakness of diffuse sensors: “seeing” a wall or machine part behind the target. Using the Triangulation Principle, a BGS sensor doesn’t just measure the intensity of light; it interprets the distance difference by detecting the specific angle at which the light returns to the receiving element. This geometric calculation allows the sensor to be programmed to identify an object at 50mm and totally ignore a bright white wall at 60mm, regardless of the background’s color or brightness.

Color Mark and Contrast Sensors

The color sensor uses RGB LEDs to act as color recognition devices. These are essential for the detection of contrast differences, such as identifying a black registration mark on a dark blue packaging film.

Convergent Beam

The convergent reflective type focuses the emitter and receiver beams at a single, fixed point in space. This allows for the sensing of very small objects, like the edge of a wafer, while ignoring everything else before or after that focal point.

Critical Selection Factors: Target Material, Distance, and Environment

The choice of sensor is dependent on a profound knowledge of the physics of the application environment since the external variables may have a major impact on the behavior of light.

- Reflectivity and Color

Every material has a unique “Reflectivity Factor.” In diffuse reflective type or modes, a matte white surface might reflect 90% of the light back to the receiver, whereas a matte black surface may reflect less than 5%, absorbing the rest as heat. This drastically shortens the effective sensing distance for dark objects. Conversely, highly reflective “mirror-like” surfaces (specular reflection) can cause “false positives” in retro-reflective sensors by reflecting the beam back just like the target reflector would. To counter this, polarized filters are used to ensure the receiver only recognizes light that has been “depolarized” by a corner-cube reflector, effectively ignoring the glare from shiny metal or plastic.

- Size and Shape of the Target

To ensure a sensor is triggered, the target has to be big enough to block or reflect a considerable amount of light beam. When the beam of light is broader than the object, e.g. a thin wire or a needle, then some light can leak out around the edges and the receiver will not be able to sense a change of state. In such situations, laser-based sensors are required since the beams of laser-based sensors are highly collimated and have a needle-thin beam that can be fully interrupted by micro-components. Furthermore, the shape matters; angled or spherical surfaces can deflect light away from the receiver (Fresnel reflection), requiring more sensitive gain settings.

- Environmental Noise and Excess Gain

Industrial environments are rarely “clean.” Airborne contaminants like dust, steam, oil mist, or heavy spray scatter and attenuate light energy. To operate through this “noise,” engineers look at Excess Gain—the ratio of light energy actually received compared to the minimum energy required to trigger the sensor. High excess gain serves as reserve power. The gold standard of harsh conditions is through-beam sensors since the light is required to pass through the fog only once. Reflective sensors, on the other hand, have to go through the contaminants twice (to the target/reflector and back), which doubles signal loss and exposes it to the risk of failure.

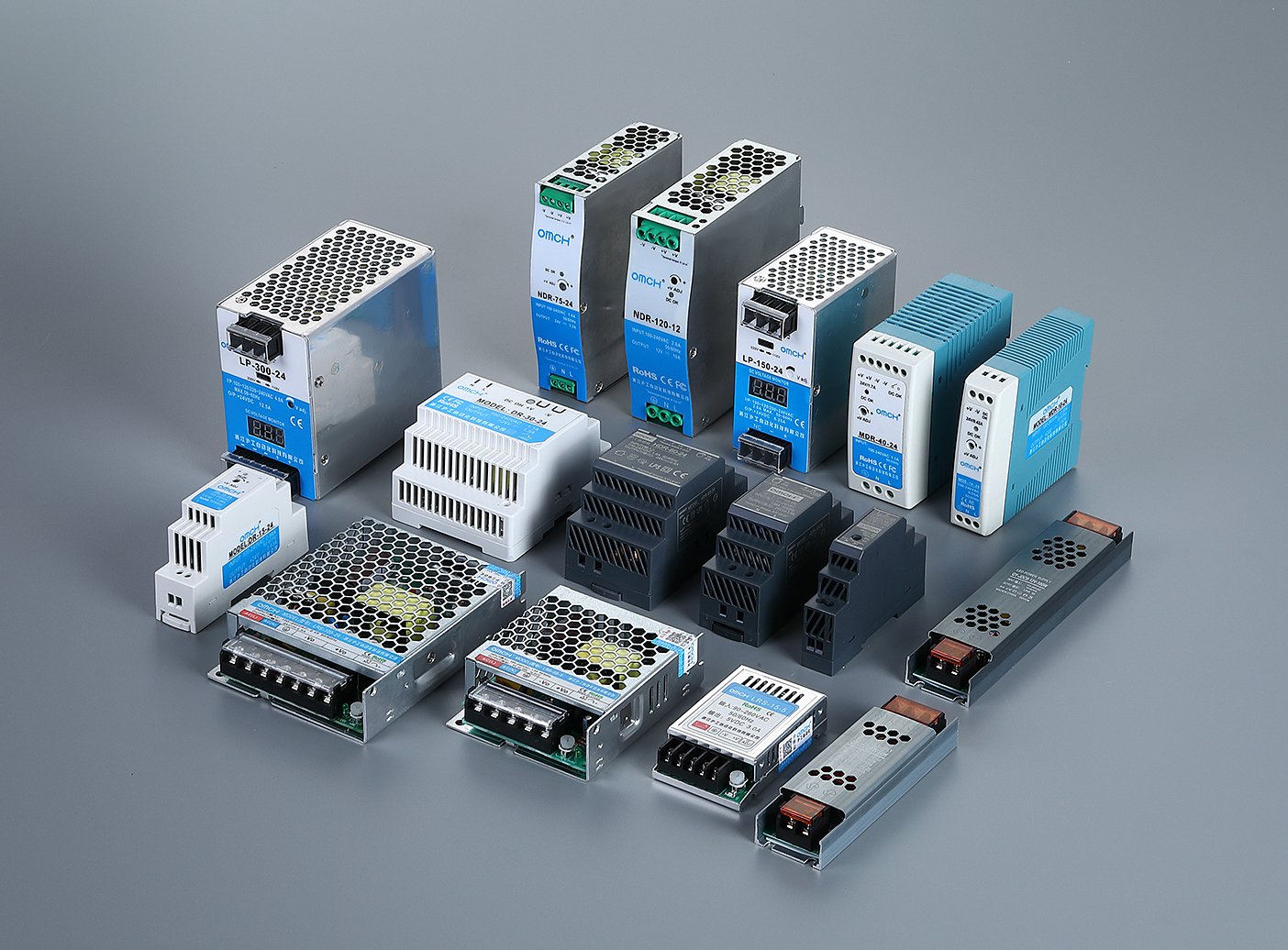

These are complicated physical aspects that a partner who has demonstrated experience. Since 1986, OMCH has been bridging the gap between advanced optical theory and the coarse reality of industry. Our designs of the best photoelectric sensor have more than 72,000 customers in 100+ countries, and have been optimized to solve certain issues such as blind zone interference and back ground clutter.

To solve the complex reflectivity issues mentioned above, OMCH has developed over 3,000 specialized SKUs that is founded on reliability and easy control. All OMCH sensors are tested in a three-phase process, including Incoming, Process, and Final inspection, in our 8,000sqm modernized plant. OMCH products are available in either a BGS sensor that is programmed to ignore brilliant backgrounds or a through-beam model with high excess gain to suit high-dust environments, and are available to global standards such as ISO9001, CE, RoHS and CCC. OMCH offers the perfect performance of milliseconds with 24/7 fast technical support, which guarantees that your critical infrastructure will remain operational, no matter how complex your sensing environment is.

Deciphering NPN, PNP, and Light-on vs Dark-on Logic

After the sensor detects an object, it has to communicate with the controller. This entails two important electrical concepts.

NPN vs. PNP (The “Polarity”)

This refers to the type of transistor used in the output stage:

- NPN (Sinking): The sensor connects the load to the negative (0V) rail. Most common in Asia and with many Japanese PLCs.

- PNP (Sourcing): The sensor connects the load to the positive (+V) rail. This is the standard in Europe and North America.

Light-on vs. Dark-on (The “Logic”)

This determines when the output signal is active:

- Light-on: The output is “ON” when the receiver sees light. (Typical for Diffuse sensors).

- Dark-on: The output is “ON” when the light beam is broken. (Typical for Through-beam sensors).

- Modern sensors often feature a “Control Wire” or a switch that allows the user to toggle between these two modes, offering greater flexibility in the field.

Troubleshooting Guide: Solving Common False Triggering Issues

Even the most designed sensors may have difficulties in the field. The first step to a fix is to know the Why of a failure:

- Mutual Interference: If two sensors are placed too close together, the receiver of Sensor A might “see” the emitter of Sensor B.

- Solution: Space sensors further apart or swap the emitter/receiver positions so they face opposite directions.

- Lens Contamination: Dust or oil film scatters the beam, leading to intermittent signals.

- Solution: Use sensors with a “Stability Indicator” LED which flashes when the light signal is becoming dangerously weak.

- Ambient Light Interference: Strong sunlight or high-frequency overhead LED lighting can occasionally bypass the sensor’s filters.

- Solution: Use a sensor with better “Stray Light Rejection” or add a simple physical shroud to the receiver.

The Future of Sensing: IO-Link and Smart Diagnostics

These devices are being changed by the emergence of optical communication protocols such as IO-Link. The functions of new sensors make it possible to transmit real-time data regarding the brightness of the LED or internal temperature. This information can be used for predictive maintenance, where the identification of the existence of target objects is not interrupted.

Instead of just outputting “Yes/No,” an IO-Link-enabled sensor can transmit real-time data regarding its health, such as:

- Internal Temperature: Detecting overheating before failure.

- Receiver Gain Levels: Alerting the maintenance team that the lens is getting dirty before it stops working (Predictive Maintenance).

- Remote Configuration: Changing sensor sensitivity or logic via the PLC software without touching the hardware.

With the advancement to more autonomous manufacturing, the incorporation of digital communication protocols will make sure that sensors will be the most dependable and intelligent parts of the modern assembly line.

Conclusion

The working principle of photoelectric sensors i.e. how the light is transformed into a quantum and how the logic of NPN/PNP outputs is obtained is one of the basic requirements of any engineer or technician in the sphere of automation. By the right selection of sensing mode and understanding of the environmental variables at work, you can develop systems that are faster, safer and more efficient.