One of the most puzzling and important decisions within automation is choosing between a Distributed Control System (DCS) and a Programmable Logic Controller (PLC). It’s a choice that determines how your facility operates, how your machines run, how your data flows, and of course, the profitability of your production line.

To declare either system a “better” choice is to ignore the reality of engineering and how nuanced it is. Your specific needs and preferences will dictate the right choice. This depends on the size of your plant, the intricacies of your processes, your budget, and your goals in the long run. For example, a system that functions perfectly in an automotive assembly plant will likely and surely cause unfortunate inefficiencies in a petrochemical refinery. The goal of this article is to cut through the noise and present to you an honest, straightforward comparison for you to arrive not at the ‘best’ system, but at the right system that matches your reality.

Architectural Differences: Centralized vs Distributed Control

In order to assess functionality, it is necessary to first analyze form. Selecting PLCs vs DCSs is not solely a matter of specifications; it is a selection of entirely different control systems approaches of how a plant should operate. In the world of industrial automation, understanding the core differences between these industrial control systems is a vital role of the engineer.

Core Philosophy: DCS vs PLC

The PLC (Programmable Logic Controller) is a robust, high-speed industrial computer system. Designed to operate in a harsh industrial environment, it was developed to replace the older relay logic units. It is the unsurpassed champion in the sphere of discrete manufacturing. It is particularly suited to high velocity, repetitive tasks such as automation control with a millisecond delay. For us, the PLC system centers around individual machines or assembly lines found in a manufacturing line. Modern PLCs manage these discrete control tasks with incredibly fast scan times, ensuring precise control.

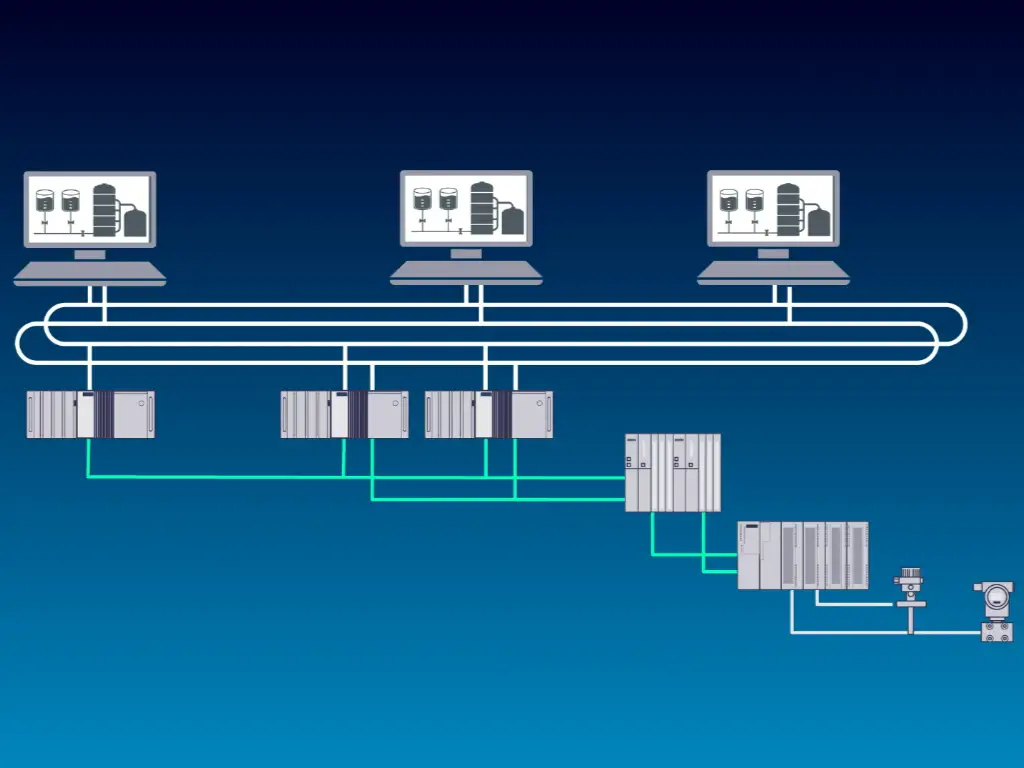

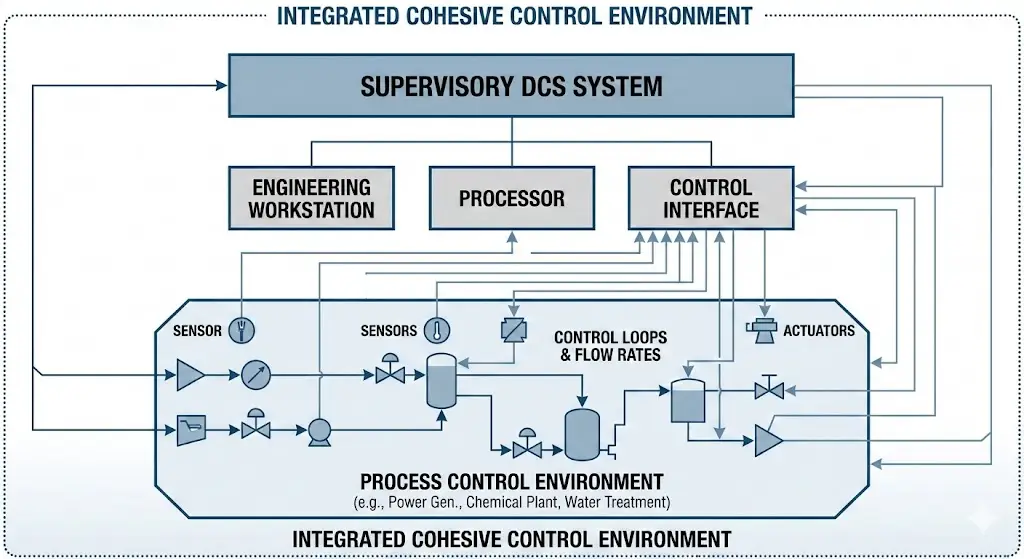

The DCS (Distributed Control System) is designed to control a process control environment in its entirety. More than a stand-alone module, it is a supervisory control system within a system that integrates a processor, control interface, and engineering workstation into a single cohesive control environment. Here, the emphasis rests on industrial processes, specifically continuous processes and complex processes like those in power generation, chemical plants, or water treatment. The DCS architecture is built for continuous operation, managing control loops and flow rates across the entire production process.

Data Architecture: Automation Islands vs. Unified Database

The key difference lies in their approaches to data acquisition and management.

- PLC as an Island: Each PLC can be calibrated as its own strong unit, or “brain.” Each PLC functions as an ‘automation island’ that can run a single machine with high efficiency—such as a compressor or a packaging unit—on its own. But in a process automation environment, having fifty islands creates complexity. Each of these islands needs to be mapped individually to set up a complicated programmable relationship to SCADA systems for visualization.

- DCS as a Continent: DCS functions as one entire system. All controllers operate with the same global multi-user data storage database. Setting up a tag inside the controller becomes available to the operator’s screen, historian, and the alarm system at the same time. Rather than a collection of individual islands, it’s a single continent. This makes it superior for process industries where the entire plant must be aware of what the specific process area is doing.

Risk Management: Centralized Failure vs. Distributed Security

The two systems approach failure differently.

- PLC Architecture: Traditionally, the PLC acts as a centralized point. If the main controller fails, the entire system section controlled by it stops. It is a “one brain, one body” relationship, potentially creating a single point of failure.

- DCS Architecture: A DCS system’s option is built around spreading out risk across different functions. Control logic is siloed. It is possible for a controller to fail without taking down an entire section. This setup is necessary to avoid a total shutdown in chemical processing or power plants, where advanced process control and energy efficiency are paramount.

Hardware Ecosystem: The Hidden Foundation of Stability

The balance made between software systems and hardware systems is difficult to define. In the case of DCS and PLC systems, the difference is made evident by taking a look inside the cabinet. These systems differ in philosophies of modularity, integration and design.

The PLC Control System Hardware Composition

The PLC rests on independent modularity for its design. You will find parts that are designed to modularly snap together to create a custom setup. Expected components are as follows:

- Processor Module (CPU): The brain. This is a fully standalone unit, and is independent of the chassis, assigned depending on the logic required to be solved and the communication demands.

- Rack/Chassis and Power Supply: This is the physical case for the modules and the unit that organizes the power supplies to each module.

- I/O Modules (Input/Output): These are interface cards that consist of Digital Input/Output (for switches and sensors) and Analog signals (for temperature and pressure transmitters). In PLC systems, there is often a mix of these modules for greater customization.

- HMI (Human Machine Interface): Typically a separate touchscreen panel that is mounted on the machine door. This is a separate piece of hardware that requires individual connection and programming apart from the PLC.

- Communication Cards: These are modules that are added to provide support for various protocols such as Ethernet/IP, Profibus, or Modbus for communicating with other devices.

The DCS Control System Hardware Composition

The DCS is sold as a pre-integrated system. The hardware is designed to function as a network rather than a standalone unit. Its ecosystem is more extensive and standardized, often incorporating hardware optimized for specific function blocks.

- Controller Cabinets: These enclose the proprietary DCS controllers. In contrast with PLCs, these contain redundancy by default: Primary and Backup CPUs that operate in sync.

- Distributed I/O Racks: These are placed in the field in a distributed manner to limit wiring. They connect back to the controller via a fieldbus which has redundancy.

- Engineering and Operator Stations: These are special industrial PCs or servers. In a DCS, the “screen” is not a peripheral; it is a hardware component of the system, and it runs the unified control software.

- Application Servers: These are devices specifically designed to act as a Historian and to control the plant-wide asset database.

- System Bus: A self-designed, high-speed communication system that interconnects all these devices, guaranteeing data reliability across the entire plant.

The Reality of Downtime: Where Systems Actually Fail

When looking at the hardware specifications, one may get caught up in that controller. It is true that DCS hardware features such superior native redundancy, where one backup controller will take over at once. That is something to write home about.

Maintenance logs tell a different story though. The controller is seldom the culprit of a plant outage. The weak spot is almost always at the system’s “edge”— the numerous field devices, the sensors, the relays, and the power supplies that drive them. A backup controller will not save the system from a corroded sensor terminal or an unsteady power supply. The automation architecture’s stability is not determined by its most expensive component (the CPU), but by the most durable, which in most systems are the field devices.

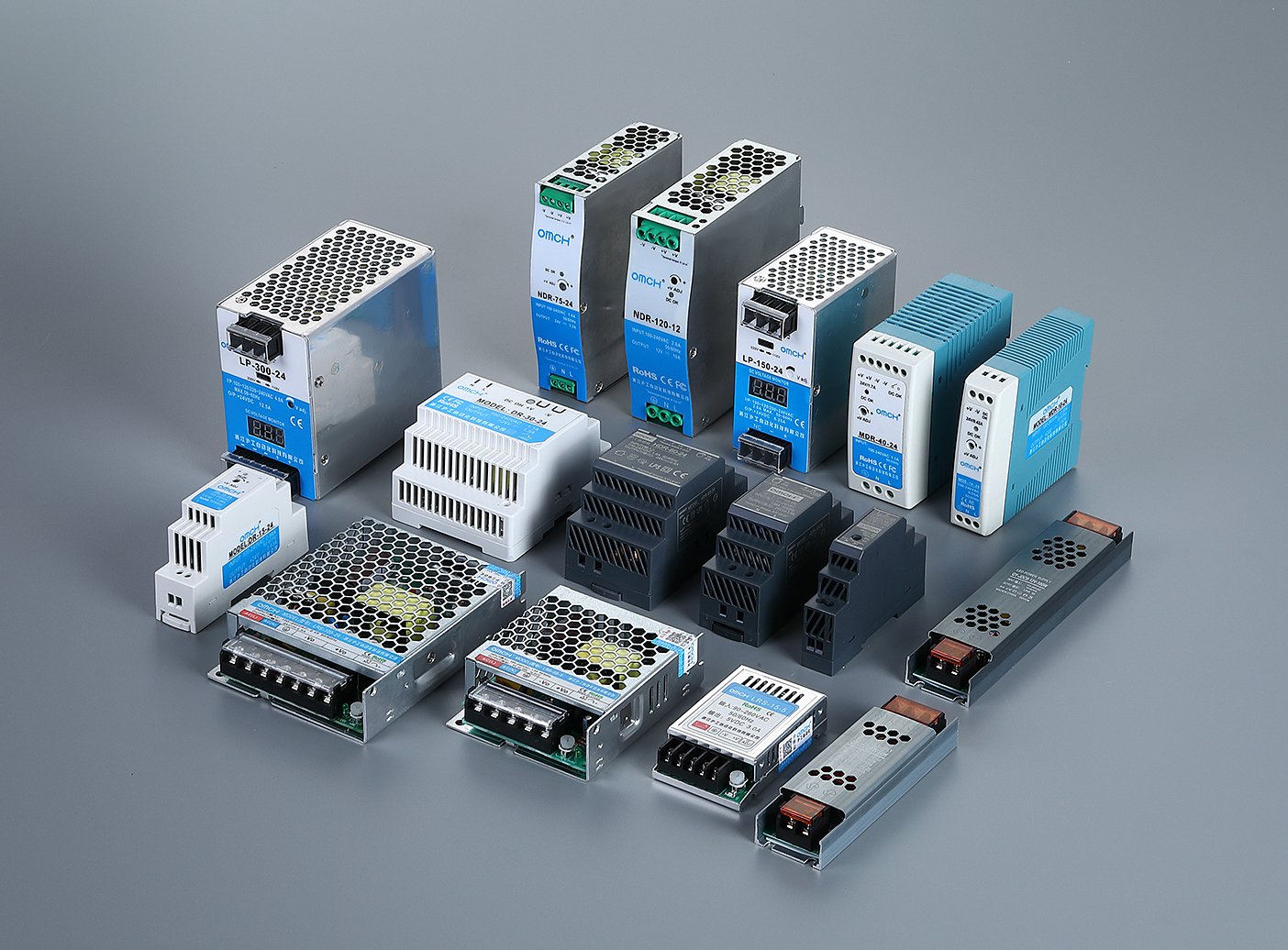

OMCH: Fortifying the Critical Edge

In the ongoing DCS vs PLC debate, one fact remains constant: the reliability of the edge determines the stability of the core.

OMCH does not manufacture the CPUs or the software licenses; we manufacture the critical industrial reality that supports them. Because the supporting hardware is standardized, you have the freedom to choose high-quality alternatives. OMCH provides industrial components—from proximity sensors to switching power supplies—that meet or exceed the specifications of major brands without the premium price tag. By utilizing high-quality standard components for the peripheral architecture of your system (whether PLC or DCS), you can significantly lower your long-term maintenance costs and ensure that spare parts are always available when you need them.

Programming & Engineering: Logic Coding vs. Configuration

A system’s costs are not limited to the hardware. There are thousands of hours of human creativity that have to be invested to make the system work. The engineering approach for PLC and DCS is fundamentally made.

- PLC Programming

Let’s start with PLC programming, where PLC engineering mostly revolves around Ladder Logic, and other programming languages within the IEC 61131-3 standard. This provides engineers with the most flexibility because they can code the controller to do just about anything. It’s very customizable.

But, there’s a downside to this blank slate. Say, for instance, you need to control a valve. That means you need to code the valve logic, create the memory tags, design the HMI screen graphic, and manually link all of it together. That’s a lot of engineering work. For complex functions, this means building the entire system from scratch, which can take a very long time. It can be a real craftsman approach; built to withstand the test of time, geared to be very customizable, but with a lot of labor required.

- DCS Configuration

The engineering work for a system predominantly focuses on system configuration, which for DCS, means there is little to no programming required. Rather, entire libraries full of function block programming tools tailored to creating Continuous Function Charts (CFCs) and function block diagrams are available.

In DCS, you don’t code a valve. You just drag a Valve Object from the library and drop it. This is a pre-assembled package that already contains everything you need, including control logic, operator screen faceplate, alarm parameters, data logging, and more. This saves a lot of engineering efforts. You don’t build the entire structure, but rather, just assemble it.

This difference affects the timelines for a project. In the case of smaller systems, or single machines, the time and overhead needed to set up a DCS is avoided. For small, one-off tasks, a PLC is much quicker to develop and deploy. Of course, the larger the system becomes, the more complicated the situation is. In the case where a project consists of 5,000 I/O points and dozens of control loops, the PLC approach of “build it yourself” becomes very expensive and susceptible to mistakes. It is. In the case of large projects, the DCS configuration model can help save thousands of engineering hours, while maintaining the same level of quality, and greatly expediting the process of getting the plant online.

| Engineering Aspect | PLC Approach (Logic Coding) | DCS Approach (Configuration) |

| Methodology | “Write from scratch” (Ladder Logic) | “Drag and Drop” (Function Blocks) |

| Flexibility | Extreme (Can do anything) | Defined (Standardized objects) |

| Setup Speed | Fast for single machines (1-50 I/O) | Fast for massive plants (1000+ I/O) |

| HMI Integration | Manual (Create tags & link graphics) | Native (Graphics pre-linked to logic) |

| Best For | Unique, custom machine operations | Standardized, repeatable processes |

TCO Analysis: Maintenance, Reliability, and Costs

The quote you receive is never an accurate representation of the cost. A Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) analysis will outline the costs of your choice over the 20-year life of a plant.

- Initial Investment (CapEx) vs. Long-Term Value

When you consider the costs involved with the hardware at the outset of the project, the PLC wins every time, offering lower initial costs. You can purchase a PLC and the relevant I/O cards for a lower initial investment than what you will pay for a DCS node. DCS hardware, system software licenses, and engineering seats come at a premium.

Yet, the financial calculations take a different turn with bigger projects. When it comes to DCS hardware, while it costs a lot, the savings from the integrations are huge. As previously noted, a DCS saves thousands of man-hours because of its preconfigured libraries and the databases being integrated. If a SCADA+PLC solution is implemented and the DCS functions (such as alarms, trending, user security, and faceplates) are replicated, the engineering costs will likely be greater than the savings that would be gained from the hardware.

- Spare Parts Availability and Maintenance Strategy

Now the projected long-term plant operation comes into focus. Energy efficiency and the mean time between failures become critical metrics.

DCS unit spare parts are typically proprietary. You have to purchase them from the original vendor, who often has a high price and a long lead time attitude. You are essentially “married” to the vendor for the entire system lifecycle.

PLC systems, while having proprietary processors as well, mostly depend on a large modular ecosystem of industrial standard parts. You are not locked to just one source, so the relays, terminal blocks, push buttons, and power supplies don’t have to come from one supplier.

Functionality in Industrial Automation

When analyzing DCS vs PLC functionality, it is very rarely just a preference. More often than not it is the design as well as the physics of the product that you are producing that will dictate the outcome.

Role of PLCs in Discrete Manufacturing Processes

PLCs in automated systems are prevalent in sectors of the economy where the output is a single unit product (e.g., car, mobile phone, bottle, box).

High-Speed Logic: In these systems, timing is critical as the packaging machine seals an average of 500 boxes every minute and requires precision within milliseconds. Should the logic slow down at all, the machine will jam.

Digital Signal Focus: These facilities operate on binary (On/Off) signals. There are often thousands of sensors that obtain the presence or absence of a part in a given area. The PLC is tuned to manage such discrete control tasks.

Ideal Environments: Automotive assembly, Bottling and Packaging, Electronics Manufacturing, Machinery OEM.

Role of DCS in Continuous Process Industries

DCS control systems are dominant in sectors where the output is a commodity (oil, gas, water, or medicine) that flows continuously, such as continuous processes.

Complex Regulation: Here, the challenge is not speed, but stability. The system must manage complex PID (Proportional-Integral-Derivative) loops to balance temperature, pressure, and flow rates. These variables interact with each other; changing the pressure affects the temperature. The DCS excels at managing these multi-variable relationships.

Batch and Recipe Management: In industries like pharmaceuticals or food processing, consistency is the law. A DCS has native, built-in support for batch management (ISA-88 standard). It manages complex recipes, ensuring that every batch of medicine or beverage is chemically identical to the last.

Ideal Environments: Chemical plants, Oil Refineries, Petrochemical plants, Water Treatment, Pharmaceutical production, Power Generation and continuous process environments where a specific process area requires constant monitoring.

Modern Convergence: Hybrid Systems and IIoT Integration

As we make our way through the 2020s, we notice the shift and convergence of the two technologies. The “Hybrid” is beginning to emerge.

Modern factories do not fall exclusively under discrete or exclusively processes anymore. A food production plant has a continuous mixing process (DCS territory) that is feeding into a high speed bottling line (PLC territory) and is then moving to batch filling.

We see the development of PACs (Programmable Automation Controllers) in this case, high-end PLCs that do a good job of handling the analog loops and more lightweight DCS save option which tends to be more affordable. Operators tend to plug high performance local PLCs into a wider DCS or SCADA network, improving local speed to the PLC while keeping supervised centralized control for the system.

Your choice from either a PLC or a DCS must consider the requirements of 2025 and beyond, where connectivity is crucial. The age of the ‘black box’ is over. Both systems utilize OPC UA, MQTT, and Industrial Ethernet. Data from the factory floor needs to be uploaded to the cloud or MES for analytics. The contemporary industry standard is to be open: the ability to derive and work with data storage from the controller the entire plant and enable predictive maintenance across the entire production process.

Conclusion: Making the Choice That Makes The Most Sense

The DCS vs PLC choice comes down to fundamental business choice of principle. It is a matter of going through the brochure and truly understanding the current working conditions for your operators and maintenance crew. If we are to summarize the comparison, these core differences need to be addressed:

| Feature | PLC (Programmable Logic Controller) | DCS (Distributed Control System) |

| Primary Application | Discrete Control (Machines, Assembly) | Process Control (Refineries, Chemical) |

| Response Time | Very Fast (5-10ms) | Deterministic / Moderate (100-500ms) |

| Architecture | Centralized / Standalone | Distributed / Integrated |

| Engineering | Customizable (High effort for large systems) | Configurable (Low effort for large systems) |

| Redundancy | Optional / Add-on | Native / System-wide |

| Cost Structure | Low Hardware Cost / Higher Integration Cost | High Hardware Cost / Lower Integration Cost |

| Maintenance | Open Ecosystem (Standard parts) | Proprietary Ecosystem (Vendor lock-in) |

There is no “better” system, only the right tool for the job. If your facility requires high-speed motion, manages discrete products, and needs flexibility, the PLC is your engine. If your facility plays a vital role in managing complex chemical reactions, requires high availability, and demands unified data across the entire plant, the DCS is your solution.

Regardless of whether you deploy a flexible PLC or a powerful DCS, the strength of your system depends on its weakest link. A multimillion-dollar control system can be brought to a halt by a failing power supply or an unreliable sensor.

Browse OMCH’s catalog of industrial power supplies, sensors, and protection components today. Build a foundation of reliability for your automation architecture with hardware that meets the highest standards of performance and durability.