The concept of automation has evolved into a luxury of the future to a necessity of survival in the unstoppable pursuit of industrial perfection. However, not all automation is equal. Even though the modern spotlight is on collaborative robots and AI-driven flexibility, there is a titan of the industry that pushes the most demanding supply chains in the world: Fixed Automation. This method, also known as hard automation, is the basis of high-volume production, which offers some level of throughput and cost-efficiency that flexible systems simply cannot match. It is the best option to global leaders who want high production rates by streamlining the manufacturing process to achieve maximum speed.

It is a 101 guide to manufacturing leaders, engineers and strategic planners who desire to know when, why and how to apply fixed automation to conquer their market segment.

Understanding Fixed Automation: Beyond the Hard-Wired Basics

The only way to understand the nature of fixed automation is to look beyond the complicated circuitry and observe the mechanical soul of the machine. In order to establish a clear definition of fixed automation, we need to consider it as a system where the order of production, the particular order of processing or assembly operations, is defined by the physical equipment layout.

When asking what is fixed automation in a modern context, it is helpful to realize that the “logic” is not just in a line of code; it is physically manifested in the cams, gears, levers, and hard-wired circuits of the machine. This guarantees that all movements are repeated with the same quality and not the variability of software-intensive alternatives.

The Music Box Analogy

Think of a traditional music box compared to a modern smartphone. A smartphone is “versatile”- it can play any song through software. Nevertheless, it needs an operating system, data and sophisticated interfaces. A music box, conversely, is “fixed.” Its song is determined by the physical pins on a rotating cylinder. It can only play one tune, but it does so with perfect mechanical reliability, requiring no software updates or boot-up time. In an industrial context, fixed automation is that music box—engineered to perform a single, high-speed task with obsessive precision.

The Characteristics of Fixed Systems

- High Initial Investment: Because the machinery is custom-engineered for a specific product, the upfront costs for design and fabrication are significant.

- Inflexibility: Changing the product design usually requires a physical overhaul of the machinery.

- Maximum Throughput: Fixed systems are designed for speed. They eliminate the “settling time” and “reprogramming lag” associated with robotic arms.

- Exceptional Consistency: With fewer variables in the movement path, the deviation between the first and the millionth unit is virtually non-existent.

Strategic Comparison: Fixed vs. Programmable and Flexible Systems

Choosing the right automation strategy is not about finding the “best” technology; it is about finding the best fit for your production volume and product variety. In order to make a sound decision, we have to classify automation into three specific types of automation pillars.

- Fixed Automation (Hard Automation)

Most appropriate when the volumes are very high and the product variety is very low. The sequence of operations is dictated by the hardware.

- Example: An automated bottling line for a specific soft drink.

- Programmable Automation

Designed for batch production. The equipment can be reprogrammed to handle different product configurations, but the changeover process often involves downtime for software reloading and physical tool swapping.

- Example: An industrial weaving machine that produces different patterns of fabric in batches.

- Flexible Automation (Soft Automation)

The most versatile tier. Flexible automation systems are capable of manufacturing a wide range of products with practically no changeover time. They are managed by central computers which change the path of the machine in real time.

- Example: A robotic welding cell in the automotive industry that can detect if the next chassis is a sedan or an SUV and adjust its welds accordingly.

Comparison Table: Automation Tiers at a Glance

| Feature | Fixed Automation | Programmable Automation | Flexible Automation |

| Production Volume | Exceptionally High | Medium to High | Low to Medium |

| Product Variety | Very Low (Single Product) | Medium (Batches) | High (Mixed Flow) |

| Investment Cost | Very High (Custom) | High | Medium to High |

| Changeover Time | Long (Requires Re-engineering) | Moderate (Hours to Days) | Minimal (Seconds) |

| Unit Cost | Lowest | Moderate | Highest |

| Primary Driver | Efficiency & Speed | Batch Flexibility | Customization |

The Economic Powerhouse: High Volume at Minimum Unit Cost

The main reason that has led to the implementation of fixed automation is the quest to achieve “Scale Economies”. Although the initial cost of a bespoke-designed fixed line may be high, the financial framework in the long term is competitive and cannot be matched by flexible systems.

The Logic of Cost Dilution

The financial model of fixed automation is constructed on two different categories of costs, the Upfront Capital Investment and the Incremental Operating Cost. In fixed systems, the huge percentage of the cost is concentrated in the first design and installation stage. But when the production line is already running, the price of producing one more unit is extremely low. By maintaining high production rates, that massive initial investment is “diluted” across millions of individual products.

The Vanishing Capital Cost

Consider it in the following manner: if a machine costs one million dollars and you only make ten items, each item costs one hundred thousand dollars. However, when the same machine is used to make ten million products, the machine cost per unit is reduced to only ten cents. Furthermore, the massive reduction in labor costs—since fewer operators are needed to manage the fixed sequence—makes this the most profitable path for mass-market goods. By automating the system, manufacturers significantly reduce their reliance on human operators, which drastically cuts recurring labor costs. The per-unit cost is much greater in robotic or manual systems since these systems have constant costs that do not reduce with volume, such as increased maintenance expenses or the logistical complexity of managing a larger workforce.

Achieving the Lowest Market Price

In products whose lifecycle is stable and long-term and whose demand in the market is high, fixed automation ultimately reaches a “floor price” that can never be achieved by competitors with flexible systems. Manufacturers are able to reach the lowest possible price point by reducing the human intervention needed to produce each unit, effectively pricing out competitors who are relying on less efficient, but more versatile, production methods.

Evaluating Industry Applications: Where Hard Automation Wins Today

Fixed automation is not a thing of the industrial revolution; it is the silent builder of the contemporary convenience. In industries where the error margin is extremely low and the volume demands are astronomical, the only way to guarantee quality and profitability is through the use of hard automation.

- The Beverage and Food Packaging Industry

In a high-speed bottling plant, performance is measured in milliseconds. Thousands of containers have to be filled, capped, labeled, and cased by machines per minute. Manufacturers make use of Continuous Motion Systems in such settings to manage complex material handling tasks. In contrast to flexible robots which might have to “pause and resume” to detect an object, fixed rotary filling stations and high-speed centrifugal feeders are engaged in an ideal mechanical dance. These lines can be operated at a rate of over 1,500 units per minute with fixed automation, and the throughput is so high that a 1% increase in efficiency will translate into millions of dollars of annual revenue.

- Medical Device Assembly

The Regulatory Stability of the medical sector is based on fixed automation. Insulin pens, inhalers, and syringes are products that need extreme accuracy and sterility. Since the production process of these devices is highly regulated by the FDA (USA) or EMA (Europe), any modification in the system will necessitate a costly and time-intensive re-validation process (IQ/OQ/PQ).

Fixed assembly lines, utilizing high-speed indexing tables and ultrasonic welding stations, provide a “locked” mechanical state. This “frozen” design is a strategic benefit; it ensures that all units are manufactured under the same mechanical conditions, which makes compliance much easier and the possibility of disastrous product recalls much lower.

- Automotive Component Manufacturing

Although the last stage of a car is a success of flexible robotics, the production of the billions of sub-parts, including spark plugs, transmission valves, and electrical connectors, is the realm of fixed automation. These sections are commonly manufactured in “Lights-out” plants where the equipment operates 24 hours a day and is not operated by humans.

Deviation is not tolerated in these sub-sectors. One spark plug with a microscopic flaw would invalidate a whole engine. Fixed systems, designed with hard mechanical stops and special inspection stations, are used to guarantee that all parts are an exact copy of the previous one, and the integrity of the global automotive supply chain is preserved.

The OMCH Advantage: Powering the Components of Fixed Lines

The construction of a high-performance fixed line must be based upon a base of components as uncompromising as the logic of the system. OMCH, which was founded in 1986, has 40 years of refinement of the hardware that makes these rigid systems come to life.

- Reliability through Rigorous Certification: Technical barriers may paralyze production in a globalized economy. OMCH products are designed to IEC requirements and supported by CE, RoHS and ISO9001 certifications. This guarantees that an OMCH component installed into a machine in Asia will be able to comply with the high safety and performance standards of a factory in Europe or North America, which gives international engineers a “trust backlink.”

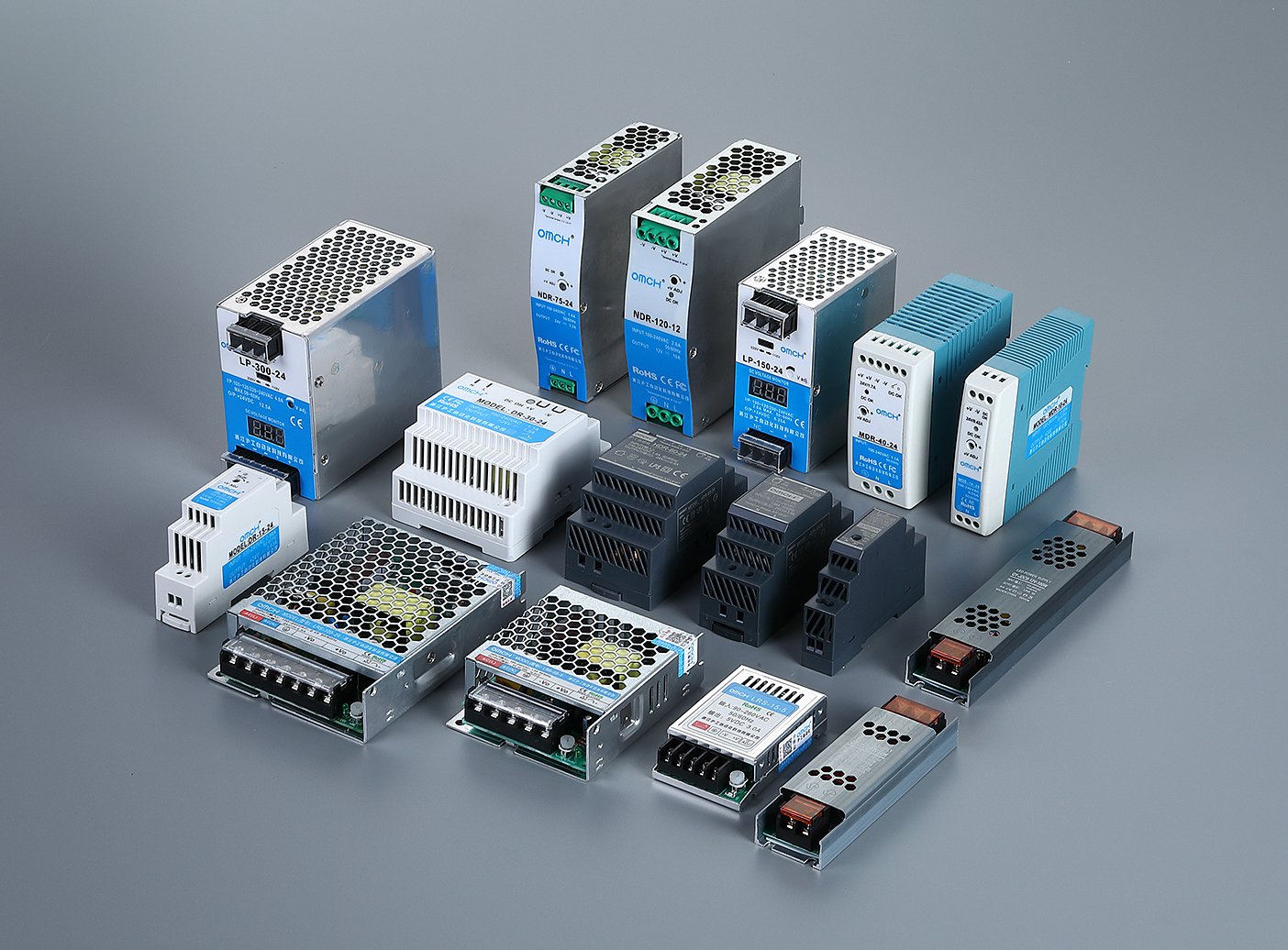

- A “One-Stop” Ecosystem (3,000+ SKUs): Fixed lines require a vast array of specialized triggers to maintain synchronization. OMCH provides an exhaustive catalog of inductive, capacitive, and long-range proximity sensors, alongside photoelectric and color-mark sensors. The engineers have the advantage of synergistic procurement by getting sensors, switching power supplies, and pneumatic components all of one, high-specification vendor so that all the parts of the “nervous system” of the machine are in the same language of reliability.

- Global Infrastructure for 72,000+ Customers: OMCH has 86 branches in China and a distribution network that covers more than 100 countries, which means that it can provide a level of support that is not available to the boutique manufacturers. Their 24/7 quick response system and one-year warranty is a safety net. In the case of a fixed automation line where each hour of downtime may cost tens of thousands of dollars, the presence of an OMCH supply chain in your area is a crucial insurance policy to your capital investment.

Digital Evolution: Transforming Rigid Hardware into Connected Systems

The most common myth about fixed automation is that it is “dumb” or “offline”. The emergence of Smart Fixed Automation is being experienced in the era of Industry 4.0.

The Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) Integration

The contemporary fixed lines are now being equipped with “digital nervous systems”. While the physical motion remains fixed, the monitoring is dynamic.

- Vibration Analysis: Sensors mounted on fixed bearing blocks can detect microscopic changes in frequency, predicting a mechanical failure weeks before it happens.

- Edge Computing: Instead of sending all data to a cloud, local edge controllers analyze the timing of a pneumatic cylinder’s stroke. If the stroke slows down by 5 milliseconds due to seal wear, the system flags a maintenance request.

Digital Twins for Fixed Assets

Digital twins of fixed lines are now developed by engineers. Manufacturers can optimize the speed of the line even faster than it was previously believed possible by simulating the mechanical stress on a custom-designed cam before it is even machined. This combination of fixed automation with 99.9% OEE (Overall Equipment Effectiveness) is made possible by this combination of “rigid hardware” and “fluid data”.

Strategic Implementation: Assessing If Your Factory Is Ready

The management should carry out a stringent “Readiness Audit” before signing the purchase order of a fixed automation system. Your facility must meet specific production requirements to ensure the investment pays off.

- Product Maturity and Design Freeze

Is your product design at least 12 months old? Fixed automation despises “version 1.1.” You will have to wait if your R&D team intends to change the dimensions or material of the product next quarter. Fixed systems require a Design Freeze as a requirement.

- Demand Forecast Certainty

Fixed automation needs a “Low Mix, High Volume” (LMHV) environment. When your sales team is unable to assure a multi-year volume that is above the breakeven point, the financial risk of stranded assets is too high.

- Technical Maintenance Capability

Fixed systems are very specialized. Do you have mechanical technicians on-site that know custom-built indexing systems? A fixed line may need extensive tribal knowledge of the idiosyncrasies of that particular machine, unlike a standard robotic arm which can be easily replaced.

- The TCO and Infrastructure Maturity

Beyond the machinery itself, a factory must evaluate its “Total Cost of Ownership” (TCO) and utility infrastructure. Fixed automation lines are often heavy consumers of pneumatic power and consistent electrical loads. Does your facility have the compressor capacity to handle the continuous cycling of high-speed actuators? In addition, preparedness entails the supply chain; a fixed line is a “hungry” animal that needs a perfect supply of raw materials. When your upstream suppliers are unable to assure you of the delivery of millions of the same components with zero defects, your fixed line will experience frequent micro-stops, which will destroy your ROI.

Moreover, the introduction of these systems presupposes the change of culture towards predictive discipline. A fixed system is unforgiving unlike the manual cells where workers can “work around” minor inconsistencies. Readiness, therefore, is as much about the quality of your incoming materials and the stability of your power grid as it is about the machinery itself. It is only after the product, the volume, the staff, and the infrastructure are perfectly aligned that a factory can safely take the hard automation route that is so strict and yet so profitable.

Managing the Rigidity: Risk Mitigation and Lifecycle Strategies

The greatest drawback of fixed automation is that it lacks flexibility. These systems are hard-wired to perform one task, and therefore have distinct risks, which should be addressed by rigorous lifecycle planning.

The Challenges: High Stakes and Low Adaptability

The main negative aspects of fixed automation are associated with financial and operational inflexibility. First, there is the Initial Investment which is high. In contrast to the cost of buying a generic CNC machine, all parts of a fixed line, including the base frame and the particular pneumatic logic, are designed to order, and the initial CAPEX (Capital Expenditure) is much greater.

Second, the Flexibility is Extremely Low. In a market where consumer preferences shift rapidly, fixed automation creates a “Sunk Cost Trap.” When a product is at the end of its lifecycle or when it is subjected to a significant design change, the whole production line can be subjected to obsolescence. Manufacturers often find themselves choosing between a multi-million dollar “re-tooling” project or scrapping the entire line, which can lead to massive financial write-offs.

Mitigating the “Sunk Cost” Trap: Modular Design

To combat this, engineers are increasingly turning to Modular Fixed Automation. The strategy here is to separate the “universal” elements of the machine from the “product-specific” ones. By standardizing the machine chassis, power supply units, and master controllers (the “base”), and only customizing the “tooling”—the nests, grippers, and cams that physically touch the product—the risk is partitioned. With this model, you do not have to replace the entire asset when you want to change the product, but you can simply replace the 30% that is custom-tooled, and you retain 70% of your original investment.

Pitfall Avoidance: Proactive Maintenance vs. Reactive Downtime

The “serial dependency” in a fixed line is absolute: when a single small belt or sensor malfunctions, the whole factory floor will come to a halt. Two strategies are necessary to prevent these expensive pitfalls:

- Total Productive Maintenance (TPM): You have to abandon a “run-to-fail” mentality. TPM entails educating all the operators to identify the early warning signals such as unusual vibrations, heat, or slight changes in timing before they lead to a complete breakdown of the entire system.

- Component Standardization: One of the biggest contributors to long down time is the use of non-standard components, which are also known as the boutique components. With the use of standardized high quality parts throughout the line, there is always a replacement that is easy to install. Standardization makes inventory control easier and makes sure that a part that costs $50 does not keep a 5 million production line at ransom waiting weeks to get a custom part.

Sustainability Metrics: The Energy Advantage of Continuous Production

As we head toward 2026, sustainability is no longer a “nice-to-have”; it is a regulatory requirement. Interestingly, fixed automation is often the greenest choice for mass production.

Energy Efficiency through Mechanical Optimization

The nature of a robotic arm is that it is not very efficient in repetitive tasks since it has to move its mass (the weight of the arm) in more than one axis of motion and in many cases it uses energy to maintain its position against gravity.

Fixed automation, however, uses mechanically optimized paths. Cams and linkages use gravity and inertia to their advantage. Once a fixed line reaches its operating rhythm, the energy required to maintain that momentum is significantly lower per unit produced than a versatile but “heavy” robotic system.

Waste Reduction

Because fixed automation is so consistent, the “scrap rate” is significantly lower. In industries like semiconductor packaging or high-speed printing, the reduction in material waste contributes directly to a company’s Carbon Footprint reduction goals. Continuous production avoids the “start-stop” energy spikes associated with batch processing, leading to a smoother, more efficient power draw from the grid.

Conclusion: The Strategic Role of Fixed Automation

Fixed automation is still a pillar of the industrial environment, especially in industries where volume and consistency are the key determinants of market competitiveness. Although the emergence of flexible robotics has increased the opportunities of small-scale manufacturing, the mechanical efficiency and low unit cost of “hard” automation remains unrivaled in long-term and high-capacity production cycles.

Finally, the choice of whether to adopt a fixed system is based on the consistency of the product design and the predictability of the market demand. With these aspects in place, the combination of mechanical accuracy with the contemporary data-driven monitoring can result in a high-performing and economically viable production setting. Success in this domain is not merely about the machines themselves, but the strategic synergy between disciplined engineering, robust component selection, and proactive risk management.