The Physical Reality of Industrial AI

The industrial landscape is currently undergoing a seismic shift towards “autonomous, flexible, and zero-defect” manufacturing, driven by the convergence of AI, IoT, and edge computing. According to recent market analysis, the momentum is undeniable: Precedence Research projects the global AI market to reach $2.46 trillion by 2030, with the manufacturing sector alone expanding at a CAGR of 27.8% (Source: Precedence Research). This surge is not merely speculative; it is fueled by tangible efficiency gains. IoT Analytics reports that predictive maintenance (PdM) now accounts for 32% of industrial AI investment, capable of reducing equipment downtime by 20–50% (Source: IoT Analytics). Furthermore, the adoption of AI-driven visual quality control has pushed defect detection rates to over 95%, while Generative AI is revolutionizing design workflows, in some cases compressing development cycles from weeks to mere days.

As factories transition from single-point pilots to comprehensive “AI + Digital Twin” ecosystems, the promise of a self-optimizing production line seems within reach. Although this points toward an increasingly automated future, what is often overlooked in the present discussion of AI for industrial automation is a very simple, fundamental fact: software and hardware are mutually dependent.

To know the use cases and the development status of AI in the industrial field, you can refer to the following blogs:

| Resource Source | Topic Focus | Link |

| IBM | Strategic overview of AI in manufacturing | Read Article |

| Aeologic | Step-by-step implementation guide | Read Guide |

| Medium (Eastgate) | Transformation of industrial sectors | Read Article |

| IoT Analytics | Market insights and trends | Read Report |

The Software Imperative

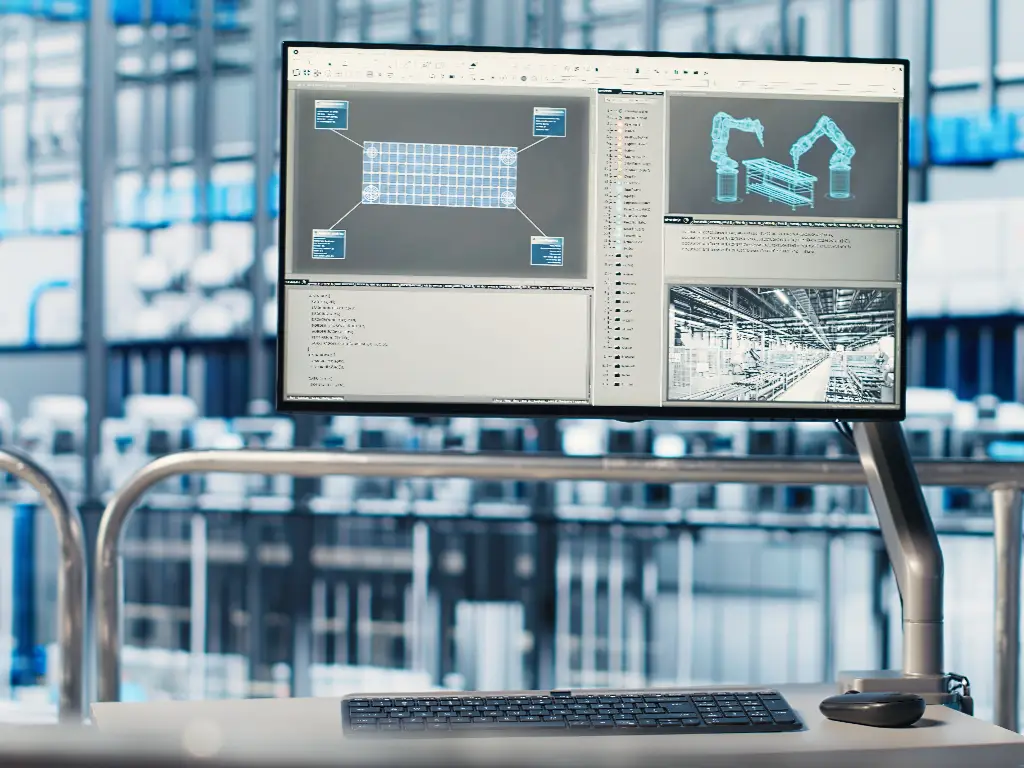

Before diving into the nuts and bolts, we must acknowledge the transformative power of the software layer. In the modern smart factory, software acts as the central nervous system, encompassing everything from the AI and machine learning models that drive computer vision to the predictive maintenance algorithms that forecast equipment failure. It extends to Digital Twins used for simulating workflows and the intricate edge computing logic required for real-time decision-making. This digital ecosystem is responsible for processing complex data streams and executing the delicate logic flow of the entire production line.

But the transition to a software-defined factory is rarely smooth. Manufacturers often face a profound cultural and technical clash: the “hardware mindset” prioritizes long the transition to a software-defined factory is rarely smooth. Manufacturers often face a profound cultural and technical clash: the “hardware mindset” prioritizes long-term stability and finalized products, while the “software mindset” demands rapid iteration and continuous delivery. This fundamental difference creates friction when traditional PLC engineers must collaborate with cloud developers, revealing a significant skills gap. Furthermore, companies often find it difficult to adapt to the long-term ROI cycles of software investment while navigating complex data sovereignty and security liabilities.

Given the immense difficulty of recruiting hybrid talent who master both industrial control protocols and cloud-native development, manufacturers should not attempt to walk this path alone. Instead, the most pragmatic approach is to partner with specialized Industrial Software Solution Providers. Rather than building an internal team from scratch, leverage the expertise of established integrators who can bridge the gap between IT and OT.

However, AI is not magic. It is a logic system that relies solely on enormous volumes of data. The intelligent automation will fail in case the sensors on your production lines are not accurate, or the power supply is not stable. To create a smart factory, it is not necessary to hire a computer scientist immediately, but to begin with a careful examination of the nuts, bolts, sensors, and switches that make the line work.

Why Algorithms Fail Without Precision Inputs

Computer science has a foundational axiom, the GIGO principle: Garbage In, Garbage Out. Although this idea is as old as the history of computing, it has never been more applicable than it is in the age of machine learning and the blending of AI capabilities. The basic distinction between the classical deterministic programming and the current probabilistic AI is the sensitivity of the data. A conventional programmable logic controller (PLC) program is based on a strict logic path; it is binary, hardy, and fairly tolerant.

An AI model—whether it relies on deep reinforcement learning, deep interactive reinforcement learning, or bayesian optimization—seeks subtle correlations and patterns in complex and often high-dimensional data, especially in dynamic environments. This requires data purity and flexible systems. If the data collection process is flawed due to poor sensor data, even the most advanced digital twins will fail to represent reality.

The Hidden Cost of Signal Noise

Signal noise is the first and the most dangerous adversary of AI reliability. The electrical atmosphere in current industrial systems is disorganized and resistant to incremental improvement. Heavy motors are switched on and off, and massive inrush currents are drawn; Variable Frequency Drives (VFDs) chop waveforms to regulate speed; and welding equipment produces arcs. All these operations cause a lot of Electromagnetic Interference (EMI) and Radio Frequency Interference (RFI).

Unless the sensors and power supplies used in the system are adequately shielded, grounded, or possess stable internal circuitry, this noise propagates through the signal cable. A high signal threshold may cause a spike in noise to be overlooked by legacy industrial control systems. However, with the integration of technology supporting the development of robust industrial wireless networks, to an AI model that is examining the waveform of the current of a motor to forecast bearing failure, that power-supply ripple is data.

An AI model that is trained on noisy data has poor generalization. Worse still, when inference is done, it can confuse electrical interference with a machine anomaly. This results in false positives—predicting a failure when there is none. This sensor accuracy issue is compounded by hardware degradation and vibration effects; sensor drift caused by thermal expansion can further skew the data analytics, impacting capabilities like autonomous navigation. When an AI system raises the alarm too often, it will be turned off, and the investment will be useless.

The Phenomenon of Data Drift

The second, more malevolent problem is the data drift associated with the degradation of components. The AI models are based on the assumption that the environment is relatively constant compared to the training data. But hardware is physically altered with time.

Take the case of a proximity sensor, which is used to track the location of a robotic arm, showcasing the capabilities of robotic systems while also facing computational challenges. Because of thermal expansion cycles, vibration loosening the mount, or aging of internal components, the sensor starts triggering a few milliseconds later than when new. The switch will still be functional to a typical automation controller since the signal will eventually reach the controller within the time limit. This drift appears to an AI that is analyzing operational efficiency or matching high-speed robotics as a fundamental change in process speed or material behavior.

When the physical parts, the sensors, switches, and relays, are not of high repeatability and environmental resistance, they are a variable of uncertainty. Thus, prior to an organization talking about critical questions regarding algorithms, it should talk about the purity of its data. This purity is obtained by making the physical production of the signal as clean, accurate and repeatable as possible while also keeping in mind the ethical use of automation highlight.

Critical Hardware for AI Data Acquisition

In order to comprehend the deep connection between industrial ai and hardware, we may use a biological analogy. The industrial parts are the nervous and circulatory systems of the AI algorithm. A brilliant mind is useless with a failing body just as a sophisticated AI model is useless without trustworthy physical inputs while adhering to ethical standards. As a result, the assessment of these underlying elements should be the initial phase of any digital transformation plan. The strong AI infrastructure is based on three hardware pillars that provide high-fidelity data:

- The “Eyes”: Precision Sensors

The sensor network, be it inductive, capacitive, or photoelectric sensors, is the main source of data. These precision sensors transform the physical world into 1s and 0s. In the case of AI, Repeatability is the key measure. When proximity sensors go off at 10mm today but shift to 12mm tomorrow, the AI will see this as an anomaly. To support autonomous mobile robots and complex tasks, sensors must provide a ground truth.

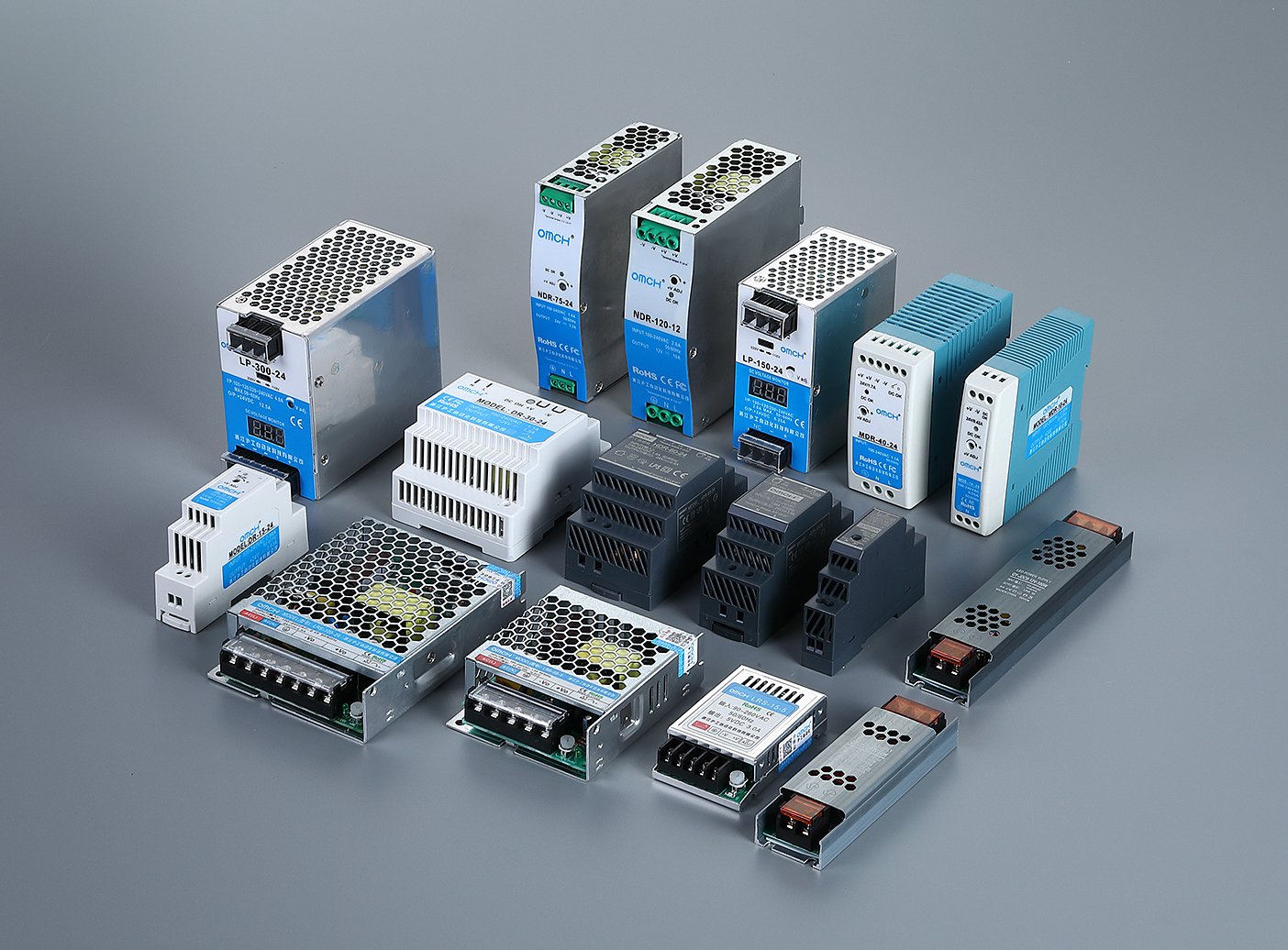

- The “Heart”: Stable Power Supplies

Compared to traditional motors, edge computing gateways and AI processors are much more fragile. They run at low logic voltages and cannot tolerate dirty power. Even a temporary drop in voltage or noise from a sub-par switching power supply can corrupt data packets. Stable power supplies serve as the barrier between the uncontrollable energy of the grid and the fragile reasoning of the AI.

- The “Touch”: Mechanical Verification

Although optical sensors are quick, they are susceptible to oil mist or steam. Limit Switches and Micro Switches are mechanical components that give the Ground Truth. They provide a physical, touch, assurance that something is where it belongs. These switches are frequently used by AI systems to cross-reference sensor data, to make sure that the digital model is the same as the physical reality.

Manufacturers such as OMCH, with a 38-year manufacturing legacy, focus on the holistic quality of this physical layer. By utilizing automated production lines and adhering to strict ISO 9001 standards, we ensure that every Power Supply provides the stable voltage required for Edge computing, and every Proximity Sensor delivers the clean, consistent data needed for training algorithms. Integrating OMCH components means removing hardware variance from your equation, providing your AI with the solid, industrial-grade foundation it needs to function reliably.

Reducing Latency for Real-Time AI Decisions

The over-dependence on cloud computing is a myth in the existing market. Although the cloud is great when it comes to long-term trend analysis, historical data warehousing and model training, it is often poorly suited to the immediate, tactical, real time decisions that need to be made on a high-speed production line.

Take the example of a bottling plant that is running at thousands of units per minute. When a vision system identifies a crack in a glass bottle, the rejection mechanism should be triggered immediately. The architecture is determined by the physics of the situation. The transmission of that image data to a server miles away, processing, and a command returned back creates latency, a delay that is physically unacceptable. Moreover, the bandwidth expense of transferring high-definition video or high-frequency sensor data to the cloud 24/7 is cost-prohibitive. The bottle has already gone past the ejection point by the time the command comes back to the cloud.

This necessitates edge computing, where AI decisions are made locally, right at the machine level. However, shifting the compute power to the edge for latency reduction exposes a new bottleneck: the response time of the hardware itself.

The Physics of Response Time

If the edge computer processes a decision in 2 milliseconds, but the sensor detecting the bottle has a response latency of 10 milliseconds, the system is inefficient due to the inability to handle repetitive tasks efficiently. High-speed automation requires a synchronization of speed across the entire chain.

- Switching Frequency: The switching frequency of inductive and capacitive sensors should be high to detect high-speed movements without missing a beat. When a gear is rotating at 3000 RPM, the sensor should be capable of turning on and off within a short period of time to count all the teeth.

- Electrical Response: Electric power supply should be able to respond to dynamic loads (rapid load changes). A rejection actuator fires, and pulls a spike of current. This spike should be stable in voltage supplied by the power supply to prevent the AI sensors to brown out.

Here, the technical specifications of the compontry, which are usually ignored in favor of software specifications, are critical. The speed of real-time AI is limited to the slowest physical element.

The Physical Trigger for Vision

Furthermore, in the implementation of vision systems and computer vision applications, the “Trigger” is vital. An expensive AI camera is useless if it takes a picture at the wrong moment, and its functionality can be improved to achieve a broader range of applications. It relies on a humble photoelectric sensor or micro-switch as a camera trigger to tell it when to look. If that trigger sensor has trigger jitter of even a few milliseconds, the object will not be centred in the frame, and the AI will fail to identify the defect. Thus, vision-system timing is entirely dependent on the accuracy of the simple trigger switch.

Retrofitting Legacy Systems: Implementing AI in Brownfield Factories

The utopian dream of the Smart Factory (Industry 4.0) tends to portray a greenfield location with a clean and shiny new set of interconnected equipment communicating through modern standards. This is economically out of touch with reality. Most of the world’s manufacturing is done in brownfield locations, or factories that are equipped with machinery that is 10, 20, or even 30 years old. These are legacy machines, which are strong mechanical workhorses, yet are frequently digitally mute. Their PLCs are based on old protocols and their internal logic is frozen, limiting their full potential to integrate into contemporary manufacturing workflows.

| Feature | Full System Replacement | Overlay Sensor Network (Retrofit) |

| Cost (CapEx) | High (Complete new machinery) | Low (Targeted component addition) |

| Installation Time | Weeks/Months (Line stoppage required) | Days/Hours (Minimal disruption) |

| Risk | High (Rewriting core logic code) | Low (Independent of old control loops) |

| Data Access | Full integration | Parallel stream via IoT Gateway |

| Ideal For | New Production Lines | Legacy/Brownfield Sites |

Replacing and ripping these machines to introduce AI is hardly cost-efficient; the capital expenditure (CapEx) would kill the margin. Moreover, trying to rewrite an old PLC to export data is a dangerous undertaking, as this process requires a comprehensive view of the whole system. A single misplaced line of code can put the line on hold for weeks.

The practical one is the Overlay Sensor Network. This is a method of putting a contemporary digital face on an old mechanical timepiece. Rather than trying to rewrite the complicated and dangerous code of an old PLC, engineers can add a second layer of sensors and switches that do not depend on the control loop of the machine.

This plan includes non-invasive sensing, including the addition of new photoelectric sensors to the conveyor to count throughput, or magnetic sensors to cylinders to measure cycle time, and connecting them to a modern IoT gateway. This forms a parallel stream of data. The old machine is still running as it has always been, but the new overlay network is taking out the data needed to analyze it with AI. This strategy significantly reduces the entry barrier of AI. Nevertheless, it values component form factors and durability. The additional parts have to be installed in small, greasy or vibrating areas that were not originally intended to be occupied by them. This is where the dependability and small size of quality parts come in and engineers can fit intelligence into tight legacy spaces without interfering with production.

Turning Component Signals into Actionable ROI

The final question to any industrial upgrade is the Return on Investment (ROI). Why would the addition of better sensors and AI save money? The solution is to shift away to predictive maintenance (fixing it before it breaks). This prevents maintenance costs from spiraling and ensures operational efficiency.

Predictive maintenance is fundamentally a practice of studying the derivative of component behaviour the rate of change with time.

Take an example of a simple relay or a pneumatic cylinder controlled by a Limit Switch. It could take only 500 milliseconds to make a stroke in a healthy state. The seals may wear out or the lubrication may dry up, and that time may creep to 510ms, then 520ms. This is invisible to a human operator. It is still within the acceptable range of the time-out of a typical automation system, and hence no alarm is raised.

Nonetheless, this trend can be identified by an AI model that processes the data stream of a high-precision limit switch. It sees the micro-deviations. The ROI takes two different forms:

- Prevention of Catastrophic Failure: The system reminds the maintenance personnel to change the cylinder during a scheduled break to avoid an unexpected stoppage. In the automotive or semiconductor industry, one hour of unplanned downtime may cost more than 50,000 dollars. Assuming that an AI system supported by high-quality sensors averts only one of such incidents annually, the hardware will be recouped a hundred times.

- Inventory Optimization: The majority of factories have too much inventory of spare parts since they are not aware when something will go wrong. They tie up capital in warehousing motors and switches in case. Under predictive AI, orders can be placed on parts on a Just-in-Time basis, using actual degradation data, releasing working capital.

Signal stability is needed at this level of granularity. In case the limit switch itself is inexpensive and unreliable, its mechanical variation will mask the variation of the machine it is measuring. Good quality components serve as the stable benchmark on which the health of the machine is gauged.

Preparing Your Infrastructure for the AI Era

As we look toward the increasingly complex tasks of the future, it is clear that Artificial Intelligence will play a central role. However, technological revolutions are rarely about the adoption of a single tool; they are about the integration of essential components and systems.

When we consider the future of manufacturing, it is obvious that Artificial Intelligence will be at the center stage. Nevertheless, technological revolutions are seldom concerned with the use of one tool; they are concerned with system integration.

The most advanced AI model is useless without data, and data is a creation of the physical world. The constraint of AI industrial automation in the present day is not the algorithm; it is the infrastructure. Looking ahead, future research will reveal that the factories that will be successful in this transition are not the ones that have the largest cloud contracts, but the ones that have the cleanest data.

For decision-makers, the path forward should not begin with a subscription to a cloud analytics platform. It should begin with a rigorous factory-floor audit to make informed decisions.

- Do the power supplies have enough stability to enable edge computing?

- Do the sensors have the accuracy to give noise-free training data?

- Do the mechanical switches provide deterministic reliability to provide a ground truth for years to come?

Investing in the “Hardware Layer” is the necessary prerequisite for building intelligence. By partnering with established manufacturers like OMCH, who prioritize quality control, international standards, and supply chain reliability, companies lay the concrete foundation upon which the digital structures of the future can be safely built. In the stochastic world of AI, the deterministic reliability of hardware is the only thing that keeps the system grounded in reality.