Within the huge ecosystem of industrial production, words are used interchangeably and this has caused confusion among the stakeholders, investors and even operations managers. Nevertheless, there is one difference that is the most important: the gap between producing separate, physical objects and developing blends. Discrete manufacturing meaning lies at the core of the former, representing a type of manufacturing that focuses on the creation of distinct items.

Look around your office or your home; nearly everything you see—your smartphone, your ergonomic chair, the car in your driveway, even electronic devices like your coffee maker—is a finished product of the discrete manufacturing process. It is a manufacturing method characterized by the production of individual units that can be counted, touched, and, most importantly, disassembled into their original components.

This guide provides a comprehensive deep dive into discrete manufacturing. We are going to go beyond mere definitions to discuss the complicated operational models, the importance of bills of materials (BOM), the technological infrastructure needed to support it, and how it is fundamentally different than process manufacturing.

What is Discrete Manufacturing? Definition and Key Characteristics

In its simplest form, the discrete manufacturing meaning refers to the manufacture of individual products. The word “discrete” means “separate” or “distinct.” In contrast to process manufacturers, who are concerned with formulas, recipes, and bulk quantities (such as liters of paint or tons of natural gas), discrete manufacturing is concerned with countable units.

The “Touch and Count” Rule

The simplest litmus test for this type of manufacturing process is countability. When you make products that are measured in units—100 engines, 500 smartphones, 50 aircraft wings—then you are operating within discrete manufacturing industries. These are hard products consisting of separate parts that can be recognized.

Key Characteristics

- Component-Based Assembly:

The discrete manufacturing process is essentially an assembly process. It entails the assembly of different raw materials (steel, plastic) and individual components (motors, circuit boards) and joining them. The final assembly is driven by a series of sequential steps: welding, bolting, screwing, and gluing.

- Reversibility (Disassembly):

Reversibility is a characteristic that distinguishes discrete and process manufacturing. When you are assembling a bicycle—a classic example of discrete manufacturing—and you make a mistake, you can unscrew the wheels and disassemble the frame and the handlebars. The individual parts do not lose their identity once the product is completed. In contrast, you cannot “un-bake” a cake back into its ingredients.

- High Complexity Bill of Materials (BOM):

Discrete manufacturing is based on multi-level bills of materials. A finished good (Parent) consists of sub-assemblies (Children), which consist of distinct components, which consist of raw materials. The key challenge of the discrete sector is to manage the hierarchy, revision history, and interdependencies of these parts.

- Route and Operation-Centric:

Production is defined by a “Routing.” This is a map that tells the shop floor that Part A must go to the CNC machine, then to the deburring station, then to the paint booth, and finally to the assembly line. Tracking the movement of these parts through manufacturing operations is critical.

Discrete vs. Process Manufacturing: A Comparative Deep Dive

In order to gain a real insight into the operational needs of discrete manufacturing, it is necessary to compare it with its counterpart Process Manufacturing.

Process manufacturing is common in food and beverage, pharmaceutical, chemical and oil and gas industries. Production in these industries is a “recipe” or a “formula.” After the production process is done, the individual ingredients cannot be recalled.

Although both are geared towards efficient production of goods, their logic, software requirements, and management strategies are opposite to each other.

The Comparison Matrix

| Feature | Discrete Manufacturing | Process Manufacturing |

| Primary Output | Distinct, countable units (e.g., Cars, Laptops). | Bulk quantities, mixtures, fluids (e.g., Soda, Oil). |

| Production Driver | Bill of Materials (BOM): Lists parts and assemblies. | Formula / Recipe: Lists ingredients and chemical processes. |

| Reversibility | High: Products can be disassembled for rework or salvage. | None: Once mixed/cooked, it cannot be reversed. |

| Quality Control | Visual inspection, tolerance measurement, functional testing per unit. | Lab sampling, chemical analysis, viscosity checks per batch. |

| Tracking Unit | Serial Numbers, Lot Numbers for batches of parts. | Batch/Lot numbers, Volume, Weight. |

| Change Management | Engineering Change Orders (ECO/ECN) are frequent and complex. | Recipe changes are strictly regulated and less frequent (due to compliance). |

| Inventory Focus | Managing thousands of unique SKUs and preventing shortages. | Managing shelf-life, expiration dates, and potency. |

The Software Divide

Due to these variations, a generic ERP system is hardly ever applicable to both.

- Discrete ERPs focus on supply chain logic, assembly scheduling, and CAD integration.

- Process ERPs focus on batch scaling, potency management, expiration dating, and catch-weight management (where one item might weigh differently than another).

The Grey Area: Navigating Hybrid Manufacturing Models

The real world does not always draw a black and white line between discrete and process. Many modern enterprises operate in a Hybrid Manufacturing environment, where both methodologies coexist under one roof.

Consider a beverage manufacturer.

- The Liquid (Process): The production of the soda is through the combination of water, sugar, carbonation, and flavoring. This is nothing but process manufacturing. It involves recipes, vats, and pipes.

- The Bottle (Discrete): Once that liquid enters the bottling line, the operation shifts. The bottle, the cap, the label, and the cardboard packaging are distinct units. The act of filling 10,000 bottles is a discrete process involving high-speed assembly and packaging.

The Management Challenge:

It is a known fact that a hybrid facility is difficult to control. A standard “Process ERP” can perhaps handle the mixing vats perfectly but perhaps not be able to track the inventory of bottle tops or the service schedule of the labeling machine. Conversely, a “Discrete ERP” can possibly track the bottles, but not to take into account the spoilage rates of the liquid ingredients.

The special “tier-two” software layers or advanced ERP modules often used by effective hybrid producers are capable of “modal switching” i.e. treating the first half of the factory as a continuous flow process and the second half as a discrete assembly line.

Discrete Manufacturing Production Models: MTS, MTO, ATO, and ETO Explained

Discrete manufacturing is not an entity. The product complexity, the variability of the customer demand, and the level of customization offered to the customer are the key issues that dictate the strategy that a company will adopt. These strategies are typically broken down into four major models of production.

- Make-to-Stock (MTS)

- The Model: Products are produced according to the demand forecasts and stored in the inventory until a customer order is received.

- Ideal For: High-volume, standardized products with predictable demand (e.g., consumer electronics, toys, standard fasteners).

- Key Metric: Forecast Accuracy. If the forecast is wrong, you either have dead stock (excess inventory) or stockouts (lost revenue).

- Workflow: Production is triggered by a “safety stock” level or a sales forecast, not a specific customer order.

- Make-to-Order (MTO)

- The Model: Production only begins after a confirmed customer order is received.

- Ideal For: Products with higher value or specific customization options (e.g., luxury cars, specialized medical equipment).

- Key Metric: Lead Time. The customer is ready to wait, but the manufacturer has to reduce the time of waiting to stay competitive.

- Workflow: Inventory is kept as raw materials. The trigger is the sales order.

- Assemble-to-Order (ATO)

- The Model: A hybrid approach. The manufacturer pre-assembles sub-assemblies (MTS) and then assembles the final product upon receiving a customer order.

- Ideal For: Computers (where you pick the RAM and Hard Drive), cars (picking color and trim).

- Key Benefit: It is a combination of MTS and MTO customization. A product that is considered to be “custom” can be shipped in days instead of months since the key parts are already on the shelf.

- Engineer-to-Order (ETO)

- The Model: The product is not in existence until the customer orders it. It is a process that requires special engineering and design prior to the commencement of manufacturing.

- Ideal For: Massive infrastructure projects, complex industrial machinery, defense contracts, prototypes.

- Key Challenge: Cost estimation. Since the product is not constructed previously, it is a huge risk to estimate the materials and labor needed.

- Workflow: The process starts with the Engineering Department, not the Production Floor. The BOM is created dynamically as the project progresses.

The Core Workflow: Bill of Materials (BOM) and Common Industries

In case discrete manufacturing contains a DNA sequence, it is the Bill of Materials (BOM).

The BOM is more than just a list of ingredients; it is a hierarchical structure that defines the product. A comprehensive BOM includes:

- Part Numbers: Unique identifiers for every screw, wire, and panel.

- Quantities: Exact amounts required per unit.

- Levels:

- Level 0: Finished Good (e.g., A Bicycle).

- Level 1: Major Assemblies (Handlebar assembly, Wheel assembly, Frame).

- Level 2: Components of assemblies (Spokes, Rims, Tires, Grips, Brake levers).

- Revision Status: Which version of the design is currently in production.

The Critical Role of ECNs (Engineering Change Notices)

In discrete manufacturing, products evolve. Engineers find a better material, or a supplier stops making a specific chip. The official procedure of modifying the BOM is known as an ECN. ECNs are a very important issue to manage- when the engineering team makes changes on a drawing and the shop floor continues to use the old BOM, the outcome is scrap, rework, and loss of money.

Common Industries Utilizing Discrete Manufacturing

Although virtually any physical object can be considered a sub-category of this umbrella, some industries are the so-called “power users” of discrete methodologies because of their extreme structural complexity and high regulatory demands:

- Automotive: The archetypal discrete industry. A car of today consists of more than 30,000 different components, including microscopic sensors and huge engine blocks. The ultimate of discrete management in this case is the coordination of the global supply chains to deliver Just-in-Time (JIT) and Just-in-Sequence (JIS). This guarantees that the particular color of a door panel will reach the assembly station at the exact time that the particular chassis is passing through the line, reducing the cost of inventory on-site.

- Aerospace & Defense: This sector operates on high-complexity, low-volume models (often ETO or MTO). In addition to assembly, the absolute requirement is traceability. All bolts and composite wing flaps should possess a “digital birth certificate.” In case a component fails during flight, discrete systems need to enable investigators to trace that particular part to its heat number of raw material and the technician who calibrated the torque.

- High-Tech & Electronics: Characterized by massive BOMs and incredibly short product lifecycles. The main problem in this industry is the control of component obsolescence and “clockspeed.” Since the tastes of consumers change in months, discrete manufacturers have to be nimble enough to clear old Rev A parts and add Rev B processors to the production line without stopping the production line or suffering huge write-offs.

- Industrial Machinery: Creating the robots, CNC machines, and specialized equipment that empower other factories. This is typically an Engineer-to-Order (ETO) environment where the design and manufacturing phases overlap. Success depends on the seamless integration of PLM (Product Lifecycle Management) and the shop floor, ensuring that custom engineering tweaks are reflected in the assembly instructions in real-time.

Strategic Benefits: Why Optimize Your Discrete Production?

Why invest millions of dollars in ERPs, automated lines, and consultants to optimize their discrete processes? The competitive advantages of discrete manufacturing are difficult to imitate since when optimized, they offer competitive advantages.

- High Granularity of Cost Control

In process manufacturing, it is hard to say exactly how much electricity went into one specific gallon of paint. In discrete manufacturing, you can track cost down to the penny. You know that Product A took 14 minutes of labor, 12 screws at $0.05 each, and 30 minutes of machine time. This granular data allows for precise pricing strategies and margin analysis.

- Agility and Customization (Mass Customization)

Consumers in the modern world desire customized products. With optimized discrete manufacturing, it is possible to achieve “Mass Customization” – the production of customized products at almost mass-production efficiency. With the help of ATO models, a factory is able to manufacture 1,000 variations of a product on the same line without much downtime.

- Traceability and Compliance

In the case of such industries as medical devices or automotive, safety cannot be compromised. End-to-end traceability is possible with discrete manufacturing systems. A serial number on a completed pacemaker can be scanned and the full history of all the capacitors in it, who made it, and when it was tested can be viewed. This is necessary to comply with regulations and to effectively handle recalls.

- Waste Reduction (Lean Principles)

Lean Manufacturing (Toyota Production System) was born in discrete manufacturing. Due to the separation of parts, waste (Muda) is easier to detect. If you see a pile of inventory sitting between two stations, that is visible waste. Discrete environments are distinctly auditable to improve processes than closed-loop piping systems in process industries.

Operational Challenges in Managing High-Complexity Discrete Environments

Although there are advantages, discrete manufacturing is full of operational minefields. The very fact that there are many moving parts, both literally and figuratively, makes it prone to failure at any point that can stop a whole operation.

- Supply Chain Volatility: A discrete product is as ready as its least ready part. You can ship with 99% of the parts to build a car, but without the steering wheel, you cannot ship. This reliance on hundreds of suppliers renders the supply chain weak.

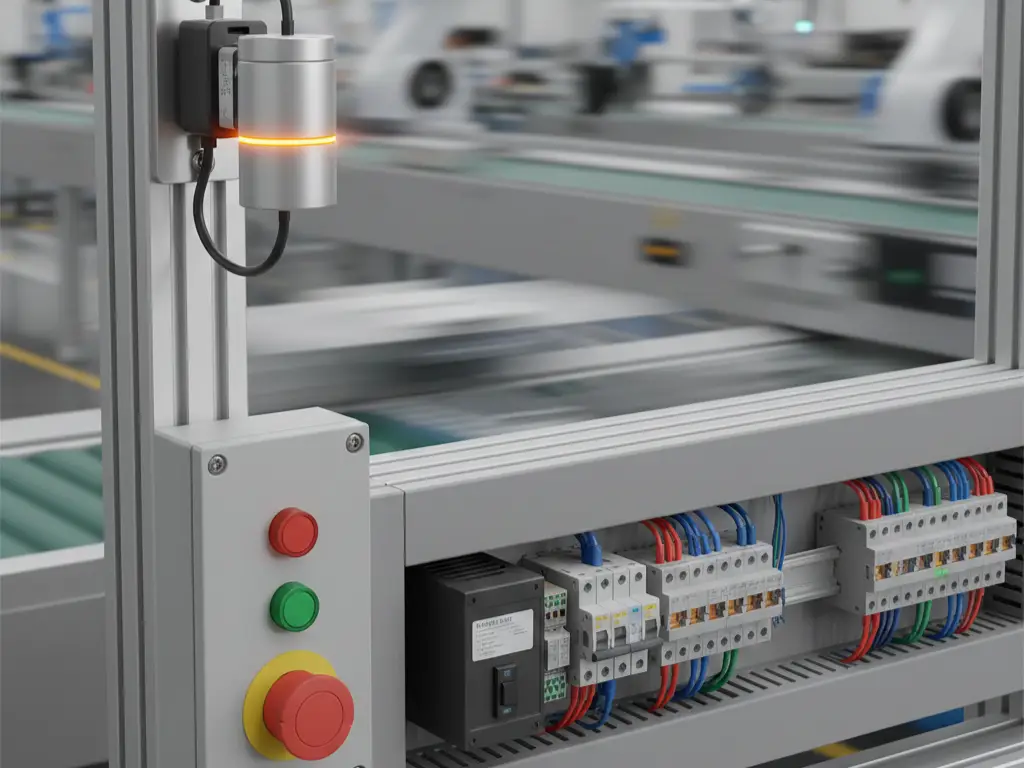

- Downtime Costs: In a high-speed assembly line, every second counts. When a sensor breaks or a conveyor gets stuck, it is not only the cost of the repair, but also the thousands of units that are not being manufactured that hour.

- Quality Consistency: Unlike a vat of chemicals which is homogenous, every single unit on a discrete line is assembled individually. This introduces the risk of human error or component variance. A switch might work on unit #500 but fail on unit #501.

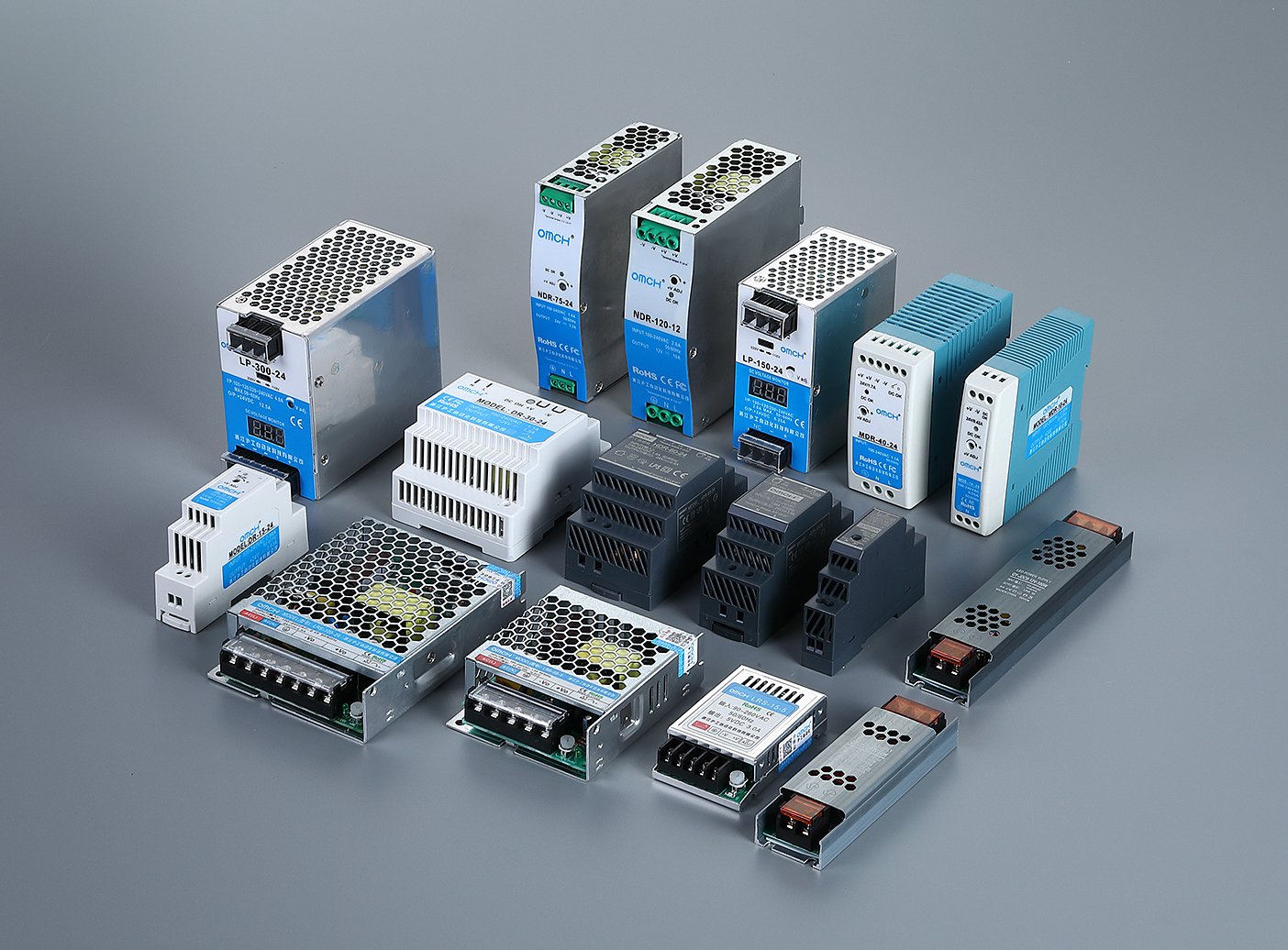

Scaling Efficiency with OMCH: Precision Components for High-Speed Assembly

The quality of your components that control your assembly line is directly related to the reliability of your assembly line in the high-stakes environment of discrete manufacturing. When a single proximity sensor fails or a power supply fluctuates, the ripple effect causes unplanned downtime, scrap, and missed delivery windows. This is where component strategy shifts from a procurement detail to a competitive advantage.

OMCH has established itself as an essential collaborator to manufacturers that are struggling with these complexities. OMCH, which was established in 1986, is not only a supplier but a full-fledged manufacturer of industrial automation and low-voltage electrical products. In the case of a discrete manufacturer, collaboration with OMCH addresses three operational pain points:

- Reducing Procurement Complexity (One-Stop Shop):

Discrete manufacturers often struggle with fragmented supply chains, sourcing sensors from one vendor and pneumatics from another. OMCH offers a massive portfolio of over 3,000 models, covering everything from inductive and photoelectric sensors to switching power supplies, breakers, and pneumatic components. This “all-in-one” capability simplifies the Bill of Materials (BOM) management and consolidates vendor lists, streamlining the procurement process.

- Ensuring Line Reliability:

Preventing defects is important in an industry where reversibility can be done, but at a high cost. OMCH has a modernized 8,000 square meter factory with 7 production lines dedicated to it, which means that all the components are produced to high international standards. Having certifications such as CE, RoHS and ISO9001, OMCH offers the hardware confidence needed to operate high speed assembly lines without worrying about component induced failure.

- Global Support for Lean Operations:

OMCH serves the Just-in-Time (JIT) requirements of manufacturers worldwide with a customer base of more than 72,000 and presence in more than 100 countries. They are dedicated to 24/7 rapid response and strong inventory management so that regardless of whether you are operating an MTO or MTS model, the automation elements needed to keep the line moving are never out of stock.

Through the incorporation of the industrial control and electrical components offered by OMCH, discrete manufacturers have the ability to strengthen the “nervous system” of their production floor, so that the physical machinery can keep up with the digital planning.

The Technology Stack: Essential ERP Features and Implementation

Discrete manufacturers need a strong technology stack to handle the complexity mentioned above. Modern BOMs and inventory levels cannot be handled using Excel spreadsheets. The digital backbone of a discrete manufacturer is the Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) system, often supported by a Manufacturing Execution System (MES).

However, not all ERPs are created equal. In choosing software in discrete manufacturing, certain features cannot be compromised:

- Finite Capacity Scheduling (FCS)

Standard planning assumes you have infinite capacity. FCS looks at the reality: “You only have 3 CNC machines and 2 welders.” It schedules production based on the actual constraints of the shop floor, preventing bottlenecks before they happen.

- Engineering Change Management (ECM)

The software must handle version control. When a BOM changes from Rev A to Rev B, the system must trigger workflows:

- Stop purchasing old parts.

- Use up existing stock of old parts (effectivity dating).

- Update the work instructions for the assemblers.

- Material Requirements Planning (MRP II)

This is the calculator. It looks at the Master Production Schedule (what you want to build) and the BOM (what it takes to build it) and tells purchasing exactly what to buy and when. In discrete manufacturing, the timing is critical to minimize cash tied up in inventory.

- Shop Floor Control (SFC)

This feature monitors the real time production status. It records the time a worker enters a job and the time they leave it by use of barcodes or RFID. This information is essential in determining the real cost of labor and giving the customers the correct delivery dates.

- Product Lifecycle Management (PLM) Integration

In the case of ETO and MTO manufacturers, the design phase is included in the lead time. Combining CAD/PLM software with the ERP will make sure that as soon as an engineer approves a design, the BOM is automatically sent to purchasing, and there will be no errors in entering data manually.

The Future of Discrete Manufacturing: Industry 4.0 and AI Integration

The days of “dumb” assembly lines are over. What is discrete automation in the modern era? It is Industry 4.0 currently transforming discrete manufacturing in a massive way. The merging of physical production and digital technology, driven by discrete automation, is forming “Smart Factories” where data analytics and AI take center stage.

- The Internet of Things (IoT)

Machines are being fitted with sensors that stream data in real-time. This would imply that in a discrete environment, the CNC machine can inform the ERP system that a drill bit is dull and requires replacement before it breaks and damages a part. This moves maintenance from “Reactive” (fix it when it breaks) to “Predictive.”

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Quality Assurance

Visual inspection is tedious and subject to human error. Computer vision systems powered by AI are currently being used to scan products on the assembly line. These systems are able to identify microscopic scratches or missing screws in milliseconds and 100% quality control is guaranteed without slackening the line.

- Digital Twins

A Digital Twin is a computer simulation of the physical product or even the production line.

- Product Twin: Engineers can simulate how a car engine will perform under heat before a single piece of metal is cast.

- Production Twin: Managers can simulate the effect of adding a new robot to the line. Will it increase throughput, or will it just create a bottleneck at the packaging station? This simulation capability allows for risk-free optimization.

- Additive Manufacturing (3D Printing)

While 3D printing started as a prototyping tool, it is moving into actual production for discrete manufacturing. It allows for the creation of geometries that are impossible with traditional machining. Furthermore, it supports the ultimate goal of “Batch Size One”—creating a fully custom product for the cost of a mass-produced one.

- The Connected Supply Chain

Discrete manufacturing in the future goes beyond the factory. The integration of blockchain and cloud enables manufacturers to have a glimpse of the inventory of their suppliers. When a supplier is out of stock of steel, the AI of the manufacturer can automatically divert the orders to an alternative supplier, and the discrete assembly process will not skip a beat.

Conclusion

Discrete manufacturing is the engine of the modern economy, responsible for the tools, vehicles, and devices that define our daily lives. The main idea, which is to put together separate components into a working unit, is easy, but the process is a cacophony of complicated logistics, engineering, and data management.

The companies that will emerge victorious as the industry shifts to high-mix, low-volume production and incorporates new AI and IoT technologies will be the ones that will master the basics: a solid BOM, a strong supply chain strategy, and the ability to adjust their production models to the constantly evolving needs of the market.